May 20, 2025 | 7 minute read

An Introduction to Discourse Analysis, Second edition, chapters 1 & 2

by

What I read

In the initial sections of this book, Gee describes the nature of language, the seven “building tasks” that structure his investigation and discussion, and why this is a valuable way of looking at the world around us.

In the introduction, Gee starts by describing how language has an intention and use that goes beyond communication. Instead, he sees the goal of language to be to “support the performance of social activity and social identities, and to support human affiliation within cultures, social groups, and institutions.” He illustrates this by means of an example, focusing on the random text from Paul Gagnon’s book, regarding the nature of what is taught in schools. This is a preliminary investigation into the use of words, and the position of those words in an argument, and how the words lead to a different form of comprehension on the part of the reader.

Gee indicates that the example used is an accusation of using English grammar politically, but “it could not be otherwise… the whole point of grammar, in speech or writing, is in fact to allow us to create just such political perspectives.”

Gee offers a brief disclaimer, that the work he is presenting is not a definitive argument for one way of thinking about discourse analysis, and that he has incorporated work of many others. He also describes that the work is about a method of research, but not in a tutorial sense. This is part of a tool of inquiry, or contains tools of inquiry, and they aren’t fixed or rigid definitions; they should be adapted for a purpose.

Gee indicates that the book has three audiences; one is students, one is people interested in language; and one is other researchers focused on discourse studies. He also describes that, in order to make the book more accessible, he has removed many footnotes or endnotes, because “people new to discourse analysis may actually read some of the material I cite.”

In Chapter 2, Gee discusses the fundamentals of “building tasks,” or the 7 elements or attributes that make up discourse analysis.

First, he describes how through language, along with all of the other parts of the human-built experience, we continually build and rebuild the world around us. This is “language-in-action.” It is a form of design, where what we say impacts the place, and so the place impacts what we say. This form of language-in-action (or -in-use) has seven building tasks.

Significance is to place emphasis on something spoken (or to simply include something that may not be necessary in content communication), which elevates it above other things that are described. Activities are the context in which language use changes. Identities are the way we build up who we are, in the space of a given moment in time. Relationships signal how we want to build social connections. Politics are assignment of blame (both good and bad), or elevating or diminishing circumstances. Connections are how things selectively become unified or relatable. Sign systems and knowledge are types of languages.

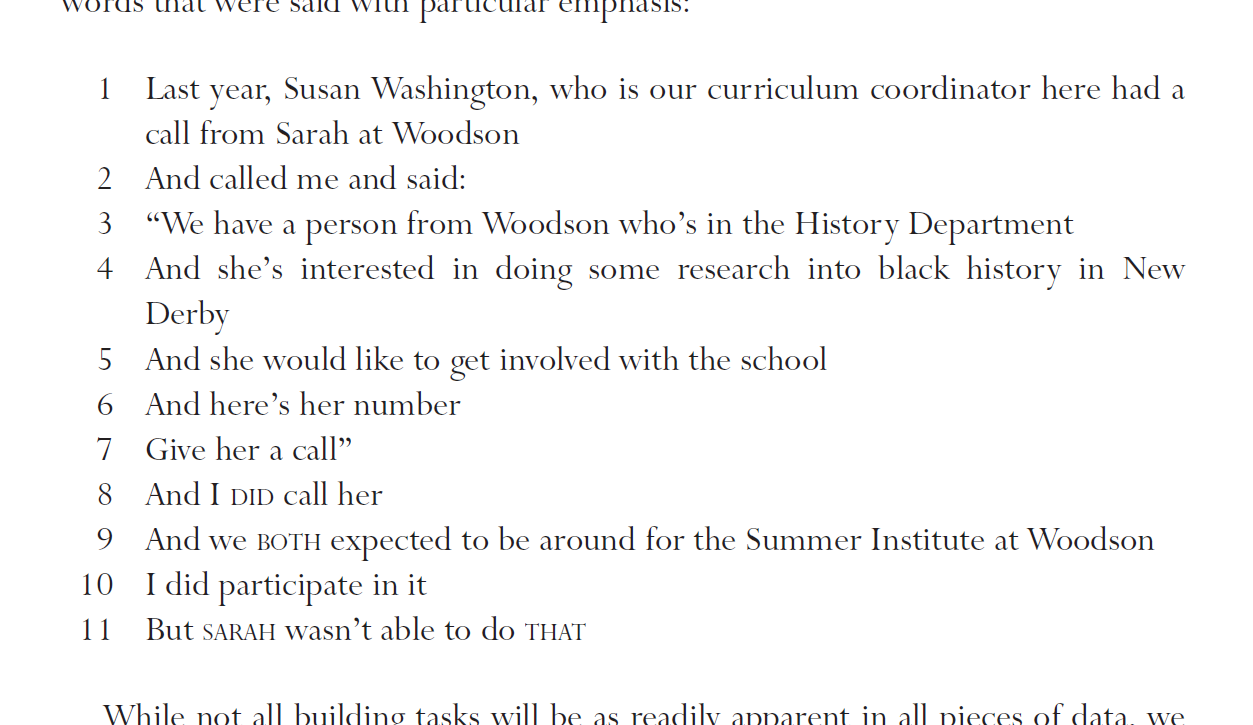

Gee then shows how these building tasks work by means of an example. The example focuses on a conversation/situation in an educational setting, where a university and middle-school teacher have had an experience, and the experience is being described in retrospect. Gee looks at a brief transcript (just 11 lines) and then unpacks that through the lens of the seven tasks.

Each of these lenses is summarized, focusing on a number of cues and clues, and interpretation, evident in the spoken (and inflected) speech. Each section begins with a question, that offers a way of considering that lens.

When Gee introduces Significance, he asks how one speaker makes a simple fact about the other into something elevated in importance. In introducing Activities, he asks about the social goal of her word choice: that she is trying to do something (in this case, contrast the way she behaved with the way another person behaved.) When Gee discuses Identities, he questions what face the speaker is trying to put on and present to others. In discussing Relationships, he asks how the speaker is indicating the way she sees the other individual, and how she wants others to see how she sees the other individual. Gee describes how Politics show up in the transcript, as the speaker works to “distribute social goods.” This is related to trustworthiness, or being a “do-er.” When discussing Connections, Gee shows how the speaker shows relevance between the various things being discussed and presented. And, when examining the transcript through the lens of sign systems and knowledge, Gee describes how under the surface is a struggle between an on-the-ground teacher and a university professor, and this is being communicated through naming language.

Gee concludes the chapter by describing how the analysis of the transcript is a form of hypothesis generation, which is supported by the data itself. This examination is not just a thought-exercise, because it uncovers some reasons why the project itself (the content) is not succeeding.

What I learned and what I think

This way of thinking feels familiar and accessible to me. I think about words and word choice, and the way people (and me, mostly) present themselves through language in different contexts. I have viewed this presentation through demeanor of artifacts and selection of artifacts (what clothes are you wearing?), but I’ve also learned that (in consulting, and probably in life), the way I show up professionally is related to dropping language related to my background, using phrases and words that show intellectual curiosity, and “reading” a room in order to understand what level of power the room wants to experience. This has always been for me a way of substantiating the way I look; it started as a coping mechanism, but it’s also become a purposeful way to juxtapose the garbage of “look how creative he is he has tattoos we are creative too by hiring him” with “wow that consultancy is actually producing valuable work and we should pay a lot of money for it.”

When I think of an “academic” analysis of data, this is what I imagine: holding data up to a very focused examination in order to probe at it from a variety of ways of thinking. When I’ve interpreted research transcriptions in the context of professional work, I’ve leveraged some, but not all, of these ways of thinking about participants. We definitely focus on significance (why did they say that—what meaning were they trying to attribute to it?) and identities (how do they view themselves?) and sign systems and knowledge (what do they know, and how are they presenting what they know?).

There’s a big difference, though, and it’s in content. We look at and “trust” the content (in as much as you can trust any form of interview data) because we need to do something with it. So far, the example used avoids the content itself, until the end (when Gee talks about hypotheses that emerge from looking at the various seven elements in the whole). This is the transcript used:

If we were analyzing this in the studio, I would probably end up with something like, “People form defensive mechanisms based on educational status, and those often turn into offensive ways of coping.” Or maybe more likely, “High school teachers have turned their jealousy of those with higher education into an ‘us vs them’ way of thinking, which results in events and activities being derailed.”

Gee describes that “These hypotheses, in turn, helped discourse researchers understand how and why the project, at various points, was failing and allowed them to help make things work a bit better.” The “how and why” isn’t part of the example in the text, so it very well may be there, but it seems to be less important than the interpretation of the language itself. I suppose another way of thinking about it is that if you have a hammer, everything is a nail, and so if you look at everything through a lens of language, language is the cause and effect.

But what about the actual actions that occurred? Or at least described as occurring? There’s no real way to consider and make conclusions or inferences about the fact that one participant did call the other, or that the other did call the other back.

I’m prematurely trying to play forward the result of an analysis like this on interview data, and struggling to see how it’s actionable. I need to not do that and let it play out in a real study. So I will.