February 12, 2026 | 6 minute read

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research, Chapter 3: Theories (and some reflections of my own)

by and

Text Exploration

In this chapter, the authors describe different types of theories that are often used to present qualitative research.

Many researchers tend to theorize by presenting what the observed in the field, with “impressive abstractions.” These typically include references to key scholars, like Latour, where the assumption is that including these other authors strengthen their argument, automatically. They don’t, and strength is only one goal of engaging with theory outside of empirical research. The main goal is to see surprises in gathered data, and engage in a conversation with other scholars. More specifically, creating a theory should be about saying something interesting.

Good theories, the authors argue, have two main goals. First, they provide a better understanding of the field; next, they allow other scholars to recognize patterns in their own work. These other scholars may be those who explore the same subfield that has been researched, or may be those focusing on social life abstractly.

The authors use a navigation metaphor, extensively, through the remainder of the chapter: a map and a compass allow someone to navigate terrain, but in different ways.

“Map theories” are substantive theories, and form the “backbone” of a discipline and the fields within it. “Compass theories”, however, are grammatical theories because they offer a “social grammar of life” and show how society is organized, irrespective of discipline. These are the “kinds of theories that graduate students often think about” and typically reference Foucault, Bourdieu, Latour, Marx, and so-on.

Substantive theories are aimed at a disciplinary-specific audience, and to be successful, these need to illustrate to that audience that what was identified during research is “transposable” to the field as a whole. This means that the explanation for what was found needs to be generalizable to the field as a whole.

Grammatical theories are “harder to pull off” because they transcend a specific discipline; they need to indicate relevance to the specific discipline, but then also show that something about navigating the larger social world is also problematic and needs to be reconsidered.

The authors recommend that there are two main ways to identify what to focus on during theory development. One is to look at “what is obviously relevant.” The other is to look at the “principles of engagement” which is what, the authors argue, makes for serious analytic work. This means that the researchers “have to take these emic preoccupations as seriously as they take the obvious theorizations of the field.”

Poor research theories are often positions as repetition of what was seen in the field, particularly the “folk theories” of the participants. Surprise should come from the content explored against and through a theory. A surprise is a theory in the making, and that theory will show that the existing “map” of the domain is flawed, how it is flawed, and what should be changed. This comes through finding patterns that aren’t in the existing map—that aren’t in the existing literature of the space itself.

The authors describe that this isn’t simply about connecting different types of literature. Instead, it is about seeing how a surprise on one map can be answered by connecting it to another map. The “best” theorizing, the authors argue, began in this way. This means that a researcher needs to be aware of the other maps, which means being widely read; “grammatical theories are always there, waiting to be read” and to contribute to grammatical theory definition, a researcher needs to continually read in and around a concept.

Reflections

I’m starting to get a sense of how my mental frame for this—for the readings, and perhaps also for scholarly work production—has been incomplete or misaligned, and it’s based on what is probably a real dumb and simple miss: I’m doing social science, with a goal of producing theories. The end-game of all of this is to create a contribution of an explanation for a social phenomenon.

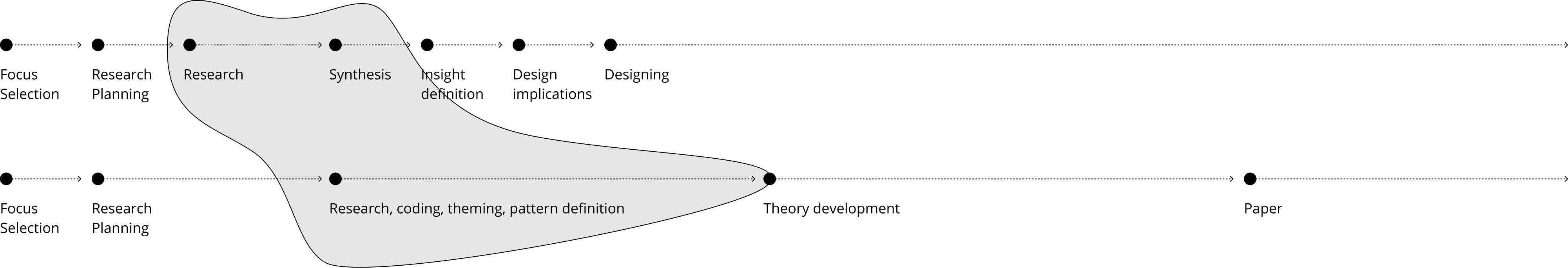

That simple idea seems kind of a pivotal center for me in moving away from qualitative research in design, and towards qualitative research about design. I think I’ve been indexing too much on the similarities of the methods and approaches, and less (or none) about the output. Designers do qualitative research; academics do qualitative research. Designers analyze and synthesize data; academics do too. And designers leverage stories and anomalous cases and eccentricities as index cases, which is at the foundation of sensemaking in scholarly work.

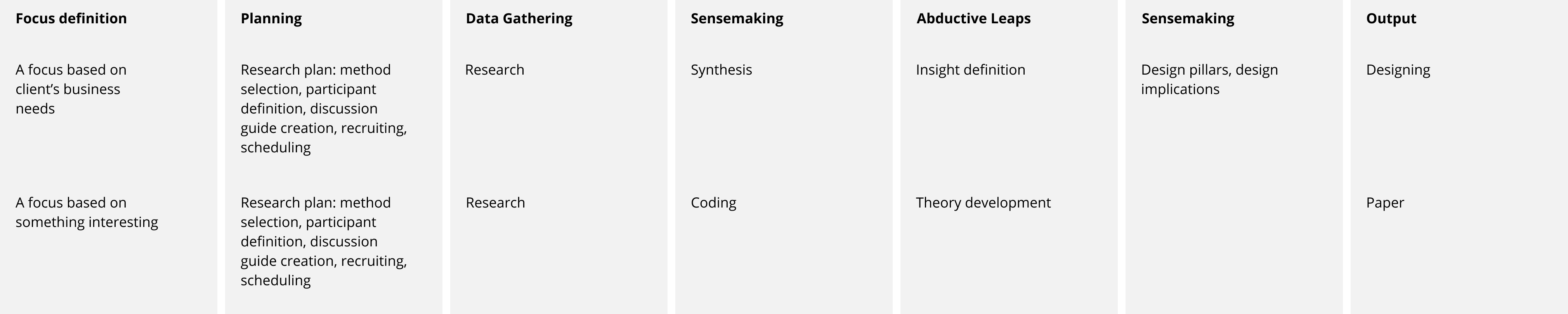

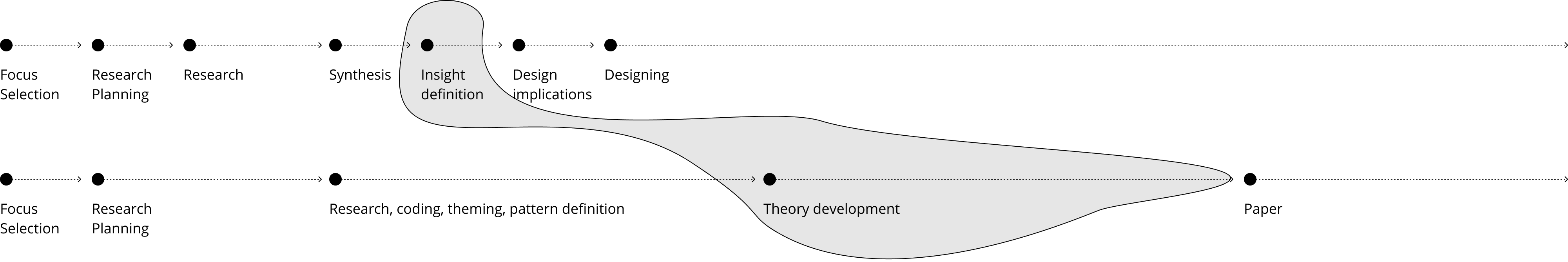

Here's an obnoxiously over-simplified diagram of what is happening here:

So here’s the tension that I haven’t picked up on until reading this, and a few other texts.

Designers create theoretical constructs as a result of the research. We call them insights, which I’ve always defined as a provocative statement of truth about human behavior. We translate those insights into “we should” statements, and then draw how those statements show up in products and services and things we make. And then we go make them.

I’ve never used the word theory in design work, ever, and I’ve never thought of any of this as theoretical, because it isn’t: the insights, which maybe generously could be mini-theories, live in a theoretical space for nearly no time. They become practical pretty much right away, and as fast as possible if design research wants to be taken seriously.

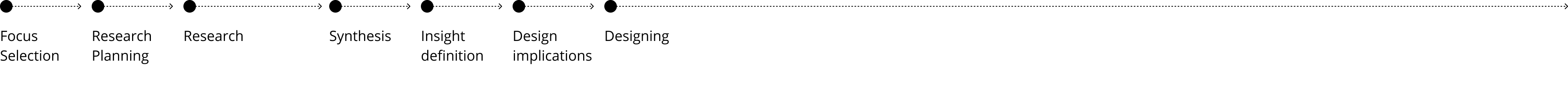

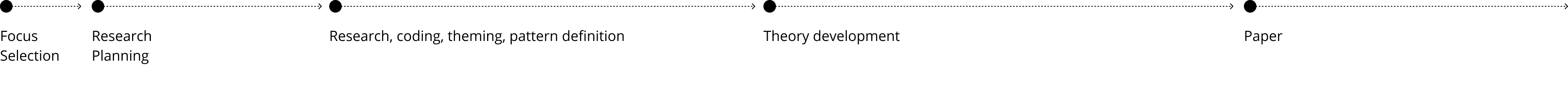

Scholarly work has misleadingly similar “steps” although with pretty different timelines:

The research is nearly the same:

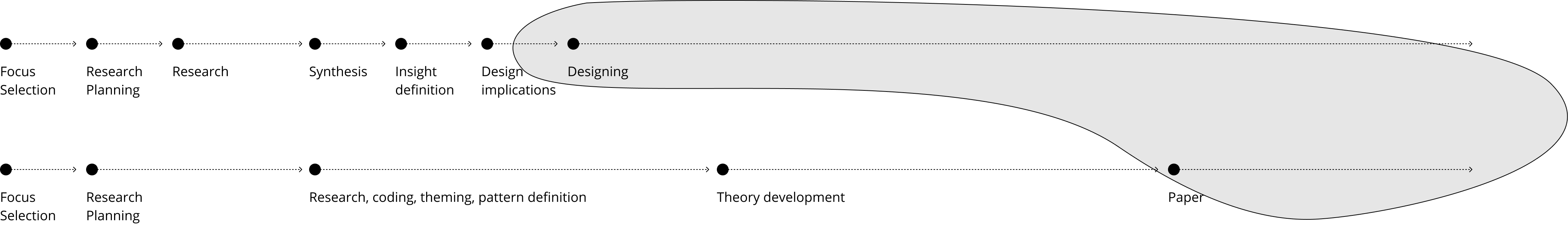

But scholarly work leads to the point of theory development as an end, and so since it’s the product, it needs to be thick—much more material than insights on a slide. The intention behind scholarly theory development and design research insights is exactly the same, but because one is a step on the way to something else, and the other is the something else, theory as end-game has to be as buttoned up and refined as product as end-game.

And then there’s the output part, which is largely where designers say “but that’s just academic” and they are right, although the “just” part is questionable:

Or, maybe another way of thinking about this is that they are actually the same, but the view of scholarly “contribution” is a parallel to the product “contribution” (which is the product, or at least the value the product is/offers/whatever).

Designers do ethnography-light; scholars do design-light.

This is sort of resonating. I remember reading an HCI-ish paper where the output was a set of requirements for a product, and they sucked, and I recall thinking “they have no business playing product manager.” They (who is they?) probably think those designers have no business playing researcher.” There’s another tension here between HCI output and social science output too, but that’s for another day.