This is from 2009 | 20 minute read

Designing in the Face of Change: The Elusive Push Towards Emotionally Resonate Experiences

Overview

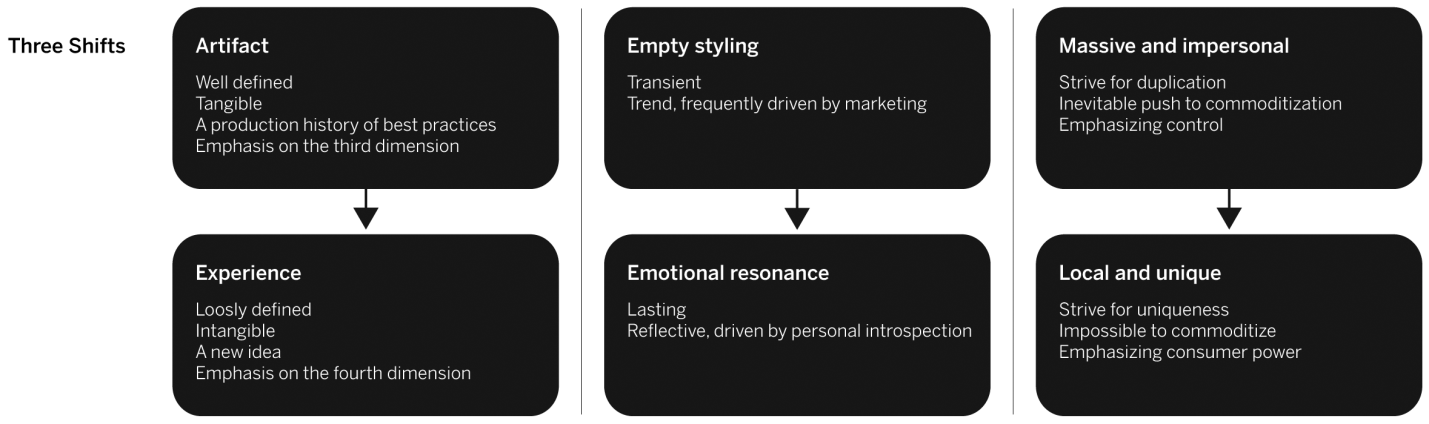

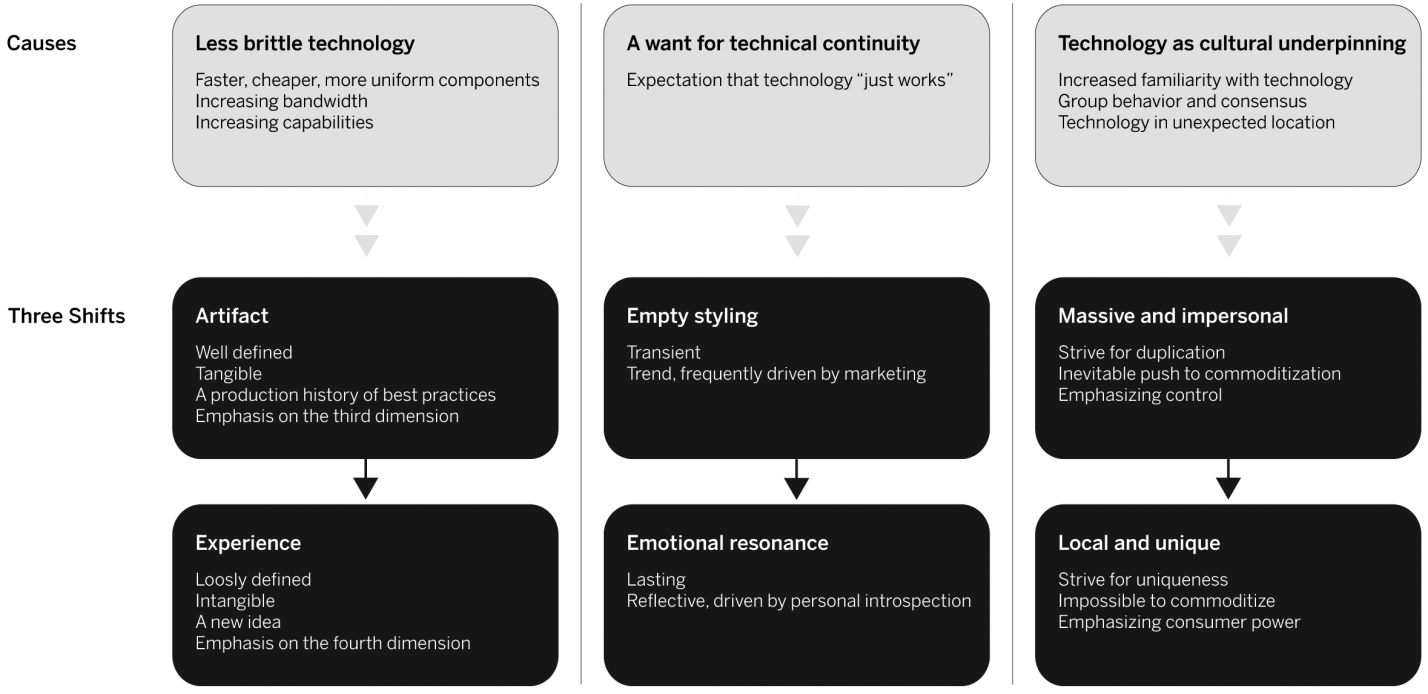

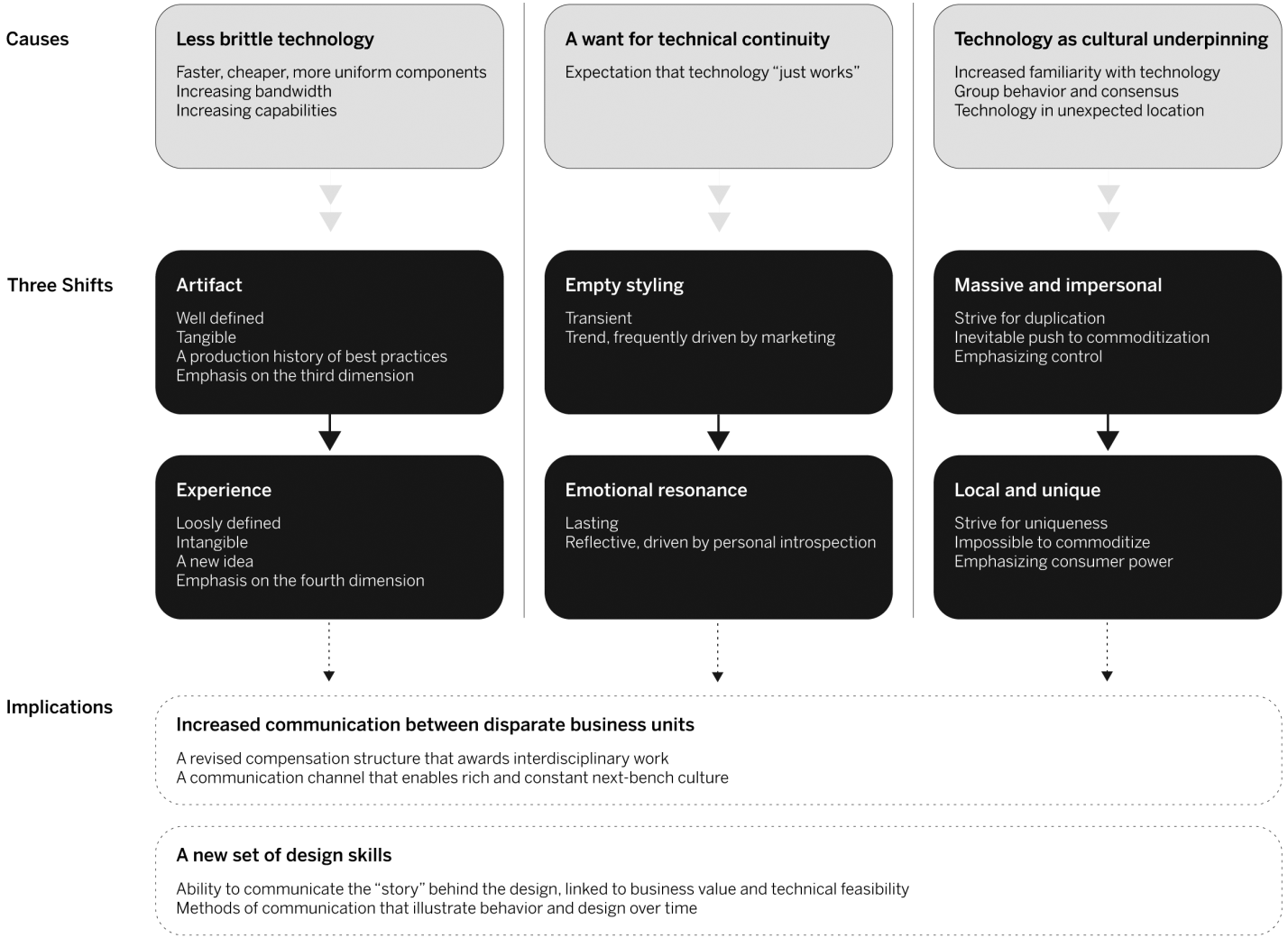

Designers are facing simultaneous and extremely meaningful shifts from artifact to experience, from styling to emotional resonance, and from the massive and faceless to the local and personal. These changes are not immediate, and are not complete; just as they didn’t begin overnight, they will continue to evolve as culture continues to morph. These shifts, however, have already had—and will continue to have—unprecedented affects on the essence of business, commerce, and trade. Each of the shifts, taken individually, tells a compelling tale of opportunity and cultural change; when considered together, the three shifts paint a picture of a world where the human condition is empowered by the connections of design and business, and where the products, systems and services that are bought and sold have a positive impact on society and on culture.

While these dramatic shifts are changing the very essence of industrialized business and culture, the industrial design process that is commonly taught and practiced hasn’t similarly evolved. Thus, as the Fortune 500 and Global 2000 realize the need for cohesive ecosystem design and search for the "end to end product experience", design consultancies are struggling to deliver more complicated offerings in shorter timeframes. A new process—a more fluid, more responsible, and more integrated design process—is necessary to solve the business and cultural problems facing today’s designers. This new process implies a push away from artifact and towards insight, with great repercussions for the traditionally “physical” field of product design.

A Shift, from Artifact to Experience

Product or Industrial Design has a celebrated history of producing beautiful artifacts, and this history is intertwined with the historic roots of mass production and business: as companies like Westinghouse or Braun made millions by producing countless objects, designers like Raymond Loewy and Dieter Rams helped create a sense of purpose for these objects in the home or in the workplace. Design as a discipline historically embraced the nature of this work, and a “product designer” was expected to envision an object and then help to produce that object, in mass. During the process of development, designers would draw and create prototypes in order to understand how an object existed “in the round”—perhaps most familiar to non-designers are the Chavant clay 1/5 scale car models, built in half and balanced against a mirror to simulate an entire vehicle. Further in the cycle of product development, advertisers would investigate how to position the products in the marketplace, and the “money shot”—the beautiful image of the object, set on a white background and lit from all directions with soft lighting—became a method of elevating the object from a simple mass produced thing to something that could be coveted and embraced, almost as a thing of beauty. The declarative focus of design, both through the creative process and through the sales cycle, was on the static object; the most celebrated designs of the twentieth century were bought, sold, used and considered as “things”.

This focus on “things” is changing, as product designers are beginning to explicitly focus on both short term and long term interactions with the artifacts they are making. This emphasis on interaction, and consideration of “time”, can be seen in all segments of product design, development, sales and marketing. In consumer goods—particularly in the areas of entertainment—consumers are enticed to purchase new electronic devices based on the “experience of use”. These products are frequently advertised on television with an emphasis on the interface instead of the physical form factor, and while product designers continue to examine the nuances of form and material, they now spend a huge majority of the creative process examining flow diagrams, use cases, usability, and other nuances of interaction. This shift is evident not only in consumer electronics. The push in the marketplace towards innovative “experiences” has created common new acronyms of UX and UE—User Experience—with centralized business units and teams of people engaged in looking at the end to end touch points between products and users. Enterprise equipment producers, sporting goods manufacturers, and even insurance providers and airlines have begun to analyze and describe the “user experience” of interacting with their products, services and systems.

A Shift, from Empty Styling to Deep Emotional Resonance

As product designers shift to consider and emphasize—and design—the interactions that occur over time, many are beginning to realize that they can imbue deep and meaningful emotional resonance in the products they create. This desire to produce meaningful products is not new: this has been the pursuit of industrial design for nearly its entire history, and designers have attempted to evoke emotions through the forms, colors, and materials that they have designed in the objects that are produced. Yet many product designers have become frustrated with the shallow and superficial “styling” that is common in the creation of mass produced artifacts. The specific product may change, but the story is the same: engineering will develop some technology, and marketing will specify a number of features. Finally, the designer will be called in to “do the plastics” or “put a pretty face on it”, and the product will go to market. Designers continually bemoan the lack of integrity in this approach, as the late addition of design is seen as lipstick on a pig and designers are implicitly viewed as lacking the intellectual capacity for the production of value in the item being produced.

Experience is intriguing to designers because experiences are, by their very nature, emotionally resonate. Put another way, people remember experiences, and they remember them on an intellectual level as well as on an emotional level. Even bad experiences become deeply woven into our memories, as we remember—often fondly, and with laughter—the time we missed the flight, or dropped the laptop in the pool, or set the microwave oven on fire. Years later, a bad product isn’t very funny, yet a bad experience, as a method of connectedness between people, seems to age well with time.

Thus, experiences have the deep meaning that product designers have long searched for, and it seems—deceptively, unfortunately –a simple change to “design experiences” instead of “designing things”.

A Shift, from the Massive and Faceless to the Local and Personal

The push towards experience is beginning to highlight a simple fact, but one that has enormous implications for those who seek to “design experiences”: human experiences are always unique. Even the most carefully crafted and planned event or interaction will always be slightly and subtly different, because the person who is engaged in the event or interaction is always slightly and subtly different. They may have woken up sad, for no reason; they may be a bit shorter or taller than was planned; they may do something unexpected, or they may even make a mistake. The production of a physical product in mass requires careful attention to tolerances, and the goal is efficient replication. Quality engineering methods, like Six Sigma, are established to ensure that the product is exactly the same, time after time. Yet experiences aren’t the same time after time; a focus on the mass-produced ignores the subtleties of human behavior and human emotion. To be more specific, and perhaps accusatory, product designers have gotten quite good at producing a repeatable and predictable product, and now the game is changing: designers are being asked to produce a positive and resonate experience, but not necessarily a repeatable or predictable experience.

Why are these major shifts occurring?

These major shifts in the business of design can be tied to three equally strong changes in culture and society.

- Basic digital technological advancements have stabilized and begun to commoditize, resulting in cheaper, faster and more effective capabilities. To see a push towards commoditization in semiconductors, we need to look no further than a common grocery store, where a talking hallmark greeting card sells for $2.99. This, synthesized with both Gordon Moore’s 1965 landmark paper, Cramming more components onto integrated circuits (Electronics Magazine) and the basic Economic theory of supply and demand, point to increased quantities of smaller transistors, with cheaper price points of digital processing power. Digital technology is no longer in its infancy, and as a result, it is less brittle, and simultaneously, it is faster and cheaper. This has positive implications for digital experiences, as they are starting to feel less arbitrary (“download this driver, move this jumper”) and more cohesive. The “seams” of the experience show less obviously, and we no longer glimpse the man behind the curtain quite as often. The combination of technical quality and usability engineering has produced technology that works fairly well, and can be relatively easily understood. This directly drives the shift from artifact to experience.

- This advanced technology is best understood by a technically savvy generation of children, teenagers and young adults who are beginning to mature and age. These new generations, at least in the United State and Europe, have access to unprecedented amounts of spending power and autonomy. The Roper Youth Report, offered by GfK Custom Research North America, suggests that “tweens” between the ages of eight and twelve have close to $10 per week to spend on their own, while teenagers have close to $25 per week to spend. Put more bluntly, “Teenagers in the United States between the ages of 12 and 19 spent more than $169 billion in 2004, $30 billion more than the entire state of Texas budget for the 2006-07 biennium, according to a study by Teenage Research Unlimited (TRU) … ‘Total U.S. teen spending exceeds the gross domestic product of countries such as Finland, Norway, Portugal, Denmark and Greece,’ said Rob Callender, the trends director with TRU, an Illinois-based consulting firm.” They also have different views of technology (many don’t “view” it at all, in the traditional sense—it’s simply a part of their existence, not something to be explicitly considered). Finally, they are socially empowered: they expect decisions to be made through communal consensus, and they expect technology to afford a sort of group-think. The Washington Post reports that teenagers operate in the ether of the internet in fickle hives: '’They're not loyal,’ Ben Bajarin, a market analyst for Creative Strategies Inc., said of the youth demographic. Young audiences search for innovative and new features. They're constantly looking for new ways to communicate and share content they find or create, and because of that group mentality, friends shift from service to service in blocs.' (Washington Post) They demand direct engagement with each other and with the corporations that are building the objects and systems they purchase. These new generations are driving the shift towards the local and personal, and away from the massive and faceless.

- Finally, consumers are increasingly expectant of products, creating a demand for emotional resonance. Consumers expect brand compatibility and integration; A recent Accenture study sent ripples through the technology community, as it reported that only 5 percent of consumer electronics that are returned are actually malfunctioning; close to 68% of the 13.8 billion consumer electronics that were returned to stores in 2007 did not meet customers’ expectations. (Accenture) if they purchase multiple pieces of hardware from a single company, they expect those pieces of hardware to communicate to each other with ease, and to support positive lifestyle experiences. The perhaps cliché phrase “brand experience” begins to transcend a single piece of technology; just as the user thinks of the interface as the product, they also consider the brand as the product.

The Response of Business

The major leaders of the Fortune 500 have responded to these shifts in various ways, and with varying degrees of success. Those that have reaped financial benefits from these shifts have made both specific, tactical changes to the way their businesses are organized and have also made strategic changes in the way they consider the products, services and systems that they provide.

One of the most apparent changes evident in large corporations that are attempting to deliver emotionally charged, resonate and personal experiences is the creation and empowerment of a “user experience” (UX) group. Ironically, those who makeup such a group commonly have no formal training in design, yet they become the “voice of the user” or the “advocate of the user” in the development of digital products. They work with external design consultants to balance both technical requirements and business requirements, and will produce artifacts that are familiar to those in both marketing and technology: an MRD, or a PRD, or a specifications document that lists, often at a feature level, what is to be built.

The existence of a formalized user experience group, and the placement of that group outside of either marketing or engineering, is a positive change that has occurred as a result of the aforementioned shifts. More importantly, these groups are being brought in closer to the beginning of a development cycle, and the people in the groups are increasingly empowered to drive product development activities and to participate in initial strategic discussions.

This centralized UX model isn’t perfect, however, and the strife between various business units is apparent inside even the most well intentioned companies. User experience professionals typically lack the visual vocabulary to present their work in a manner that is emotionally resonate, and so they become only conduits for outside vendors to deliver true, representative design solutions. This belittles their role within the corporation, and may actually position the UX group in a negative light—they may be seen as the “vendor management” organization, or “marketing lite”. Additionally, the members of a UX group typically come from a background in either marketing or usability engineering, and therefore they lack a formal and methodical creative design process. The methods used by this group in many companies are inconsistent and poorly documented, and are therefore reinvented during each project or cycle. This lack of consistency suggests a disparate level of success, and one can’t help but wonder how many project teams are left with a “bad taste” in their mouths after working with corporate UX.

Regardless of the quality of the UX offering, however, the mere presence of this group in an organization implies that the organization recognizes the three major shifts, and is working to produce resonate and emotionally relevant products. Found hand in hand with a user experience group, then, is the strategic push towards “ecosystem” design, or the “end to end product lifecycle”. As a method of addressing the above shifts, companies are considering how brand loyalty can translate to an interconnected home or workplace, where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts; when all products that are developed by a single company can talk to each other, the larger “world” of those products provides an exponential curve of utility, and the cost of change becomes increasingly large. This interconnectedness becomes a strategic method of ensuring repeat brand purchases.

Thus, we find ourselves at a place where major shifts are occurring—shifts that will likely benefit consumers, through increased emotional resonance of products, and that will benefit businesses that are able to leverage the brand value of a cohesive, connected experience across multiple touch points. These shifts have generated a number of difficult challenges, and raise large questions about the nature of our organizational structures, our design processes, and the available talent pool of designers ready to face these challenges.

The Challenge of Experience

For businesses familiar with physical product design and development, the push towards digitally-empowering experiences presents new challenges in the design and development of software, and many of these businesses may not be prepared for the difficulties that are introduced when attempting to shift from a producer of artifacts to a producer of experiences. While physical manufacturing enjoys a century long precedent of trial, error and exploration, software development is still in its relative infancy. Companies that intend to produce “hybrid” goods—both physical and digital—must now revisit all of the issues of quality assurance that they assumed were bested in the 80s, and prepare themselves to learn again what it means to deliver defect-free products. There exist established methods for improving both quality and time to market when producing digital goods, yet these methods are flawed and highly problematic, and are the subject of debate even within pure-play software companies. The approach used by most software companies is that of “patch and upgrade”, where software patches are provided to fix defects found post-release, and upgrades are offered that allow new levels of functionality. Consumers have gotten fairly used to the cumbersome process of downloading updates to their software products, but it remains to be seen if they have the patience to “patch” their physical products, too (would mom really want to “upgrade” her refrigerator?)

In addition to these pragmatic challenges related to product stability and quality, there are strategic challenges that must be approached in a more authoritative manner, from the top of the organizational structure. In emphasizing experiences that resonate across multiple artifacts, it becomes obvious that business units cannot focus on a single product anymore—the people responsible for any given product must regularly communicate with people in other business units in order to drive alignment around a central, cross product experience.

This is easier said than done, as large corporations are commonly organized around narrowly defined product lines, where members of the development team have visibility only within a given SKU or set of SKUs. If the compensation structure of a company reinforces an internal, siloed approach to product development, there is no direct motivator for an individual to explore the offerings of “competitive” business units. The result of this deeply verticalized approach to business organization on the visual and semantic “experience of use” is explicitly negative: there is little chance of the consumer enjoying a cohesive and consistent set of interaction and aesthetic paradigms when using multiple products that represent a single brand. Much like a brand is described and controlled through brand guidelines, interactions must also be unified—yet because interactions are subtle and diverse, a simple pattern library or unified taxonomy is not enough to drive consistency. Nor is a governance model—commonly used to control content development and publically-facing marketing material—appropriate for moderating interaction approaches, as the nuance of interaction are slight and deeply connected to the form and function of a given product. This challenge—the challenge of driving unified and consistent behavior in multiple product lines—is one that has few precedents for success, and those corporations that continue to meet this challenge (such as Apple or Nike) are increasingly secretive about their internal, cross-vertical development processes. Many attribute these few successes to a heavy-handed visionary at the “top” of the company; it is unrealistic to expect this type of vision in the majority of the Fortune 500 or Global 2000.

Design consultancies face equally difficult challenges, if they wish to be considered as top tier vendors for the large end to end product development described above. It is no longer enough to simply “be creative”; product design consultancies need to be able to communicate their creativity easily inside of a large organization, which requires a unique set of communication and facilitation skills. Creativity needs to be obviously and visibly linked to business value and technological feasibility, and the “story” of the design needs to be easily communicated to individuals who may not be familiar with discussing subjective topics like “behavior”, “aesthetics”, or “appropriateness”. While product designers have long-since viewed themselves as storytellers, the focus of the narrative now needs to extend beyond the physical object, and must include a tale about an interface, a brand, and ultimately the socialization process that will be used internally to drive consensus towards a given solution. Put another way, designers can no longer count on being present to “sell” their design solutions to skeptical clients or audiences—instead, various UX managers will likely continue to evangelize and “socialize” the design inside of the corporation by themselves, and they need enough communicative ammunition to become designers-by-proxy.

An Optimistic Future

The three shifts described here—from artifact to experience, from styling to emotional resonance, and from the massive and faceless to the local and personal—are all positive trends. These shifts point to a future that empowers consumers, expands the footprint of business, and generates increased revenue through meaningful product development. Additionally, these shifts tell a compelling tale of opportunity and cultural change. Corporations and design consultancies that embrace these shifts can expect to reap dramatic benefits in the future, as these changes indicate an optimistic future: one where the human condition is empowered by the connections of design and business, and where the products, systems and services that are bought and sold truly enrich the fabric of society.