This is from 2025 | 6 minute read

Academic Papers and the Dead Poets Society Effect

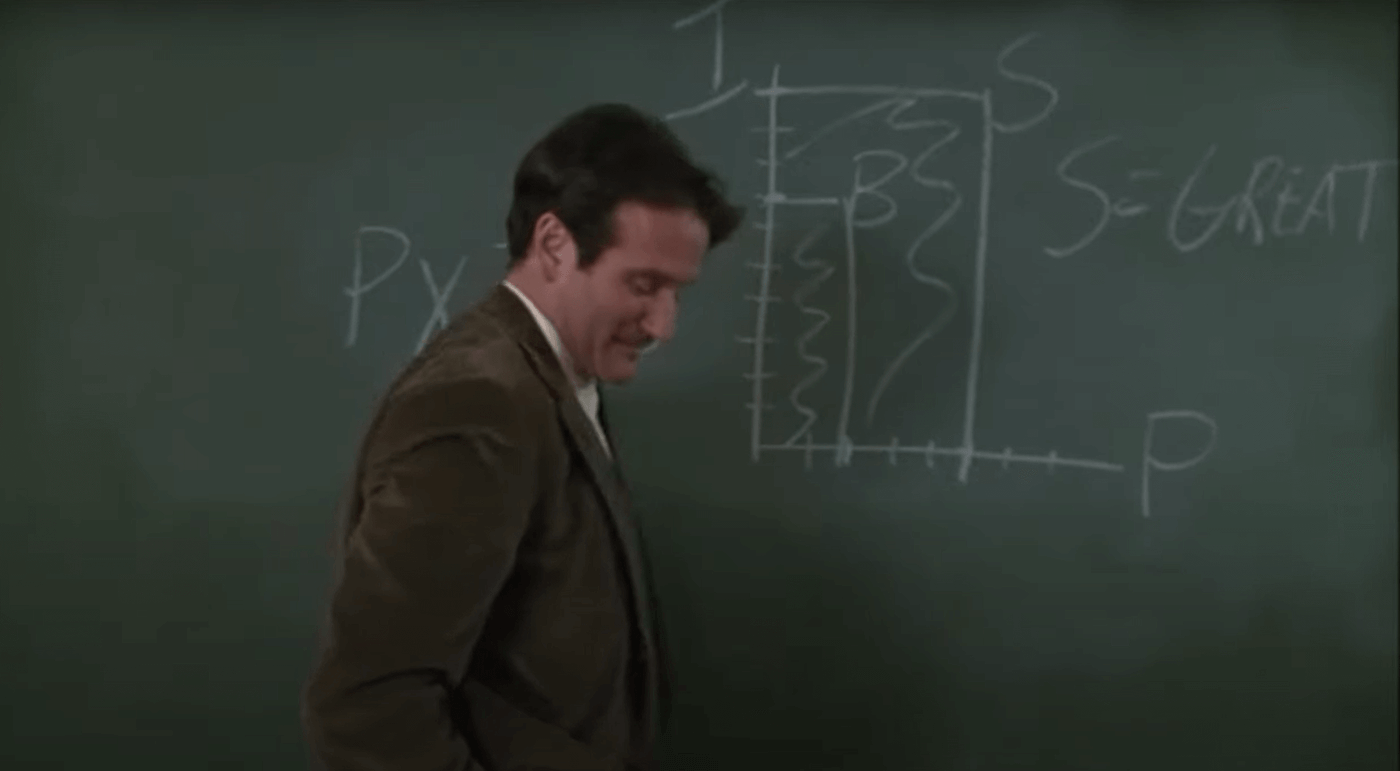

One of the most memorable scenes in Dead Poets Society is sometimes referred to as the "paper ripping" scene. At the start of the semester, Robin Williams, as Professor Keating, asks Neil, his student, to read aloud the introduction of Understanding Poetry. Neil reads,

"If the poem's score for perfection is plotted on the horizontal of a graph and its importance is plotted on the vertical, then calculating the total area of the poem yields the measure of its greatness.

A sonnet by Byron might score high on the vertical but only average on the horizontal. A Shakespearean sonnet, on the other hand, would score high both horizontally and vertically, yielding a massive total area, thereby revealing the poem to be truly great."

As Neil reads, Professor Keating draws the chart on the chalkboard:

And when Neil's done reading, Keating instructs the students to rip the pages out of the book, which he describes as "excrement." Several students are horrified. (Many are thrilled.)

As I prepare for my PhD experience, I've returned to a lot of academic literature, and much of it has content that feels an awful lot like the poetry perfection chart.

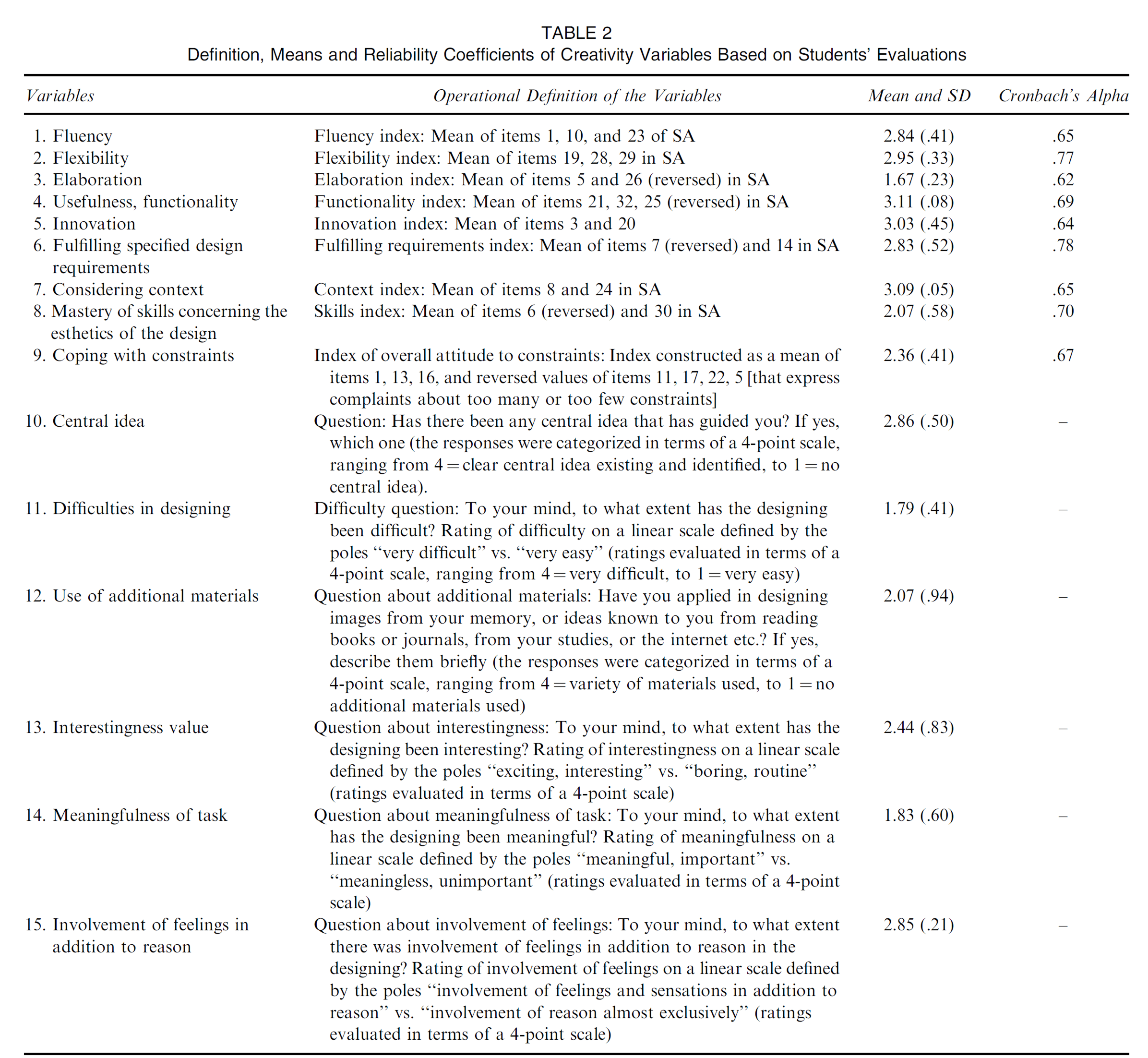

Here is a table excerpted from a paper about what motivates design students, displaying creative variables from students' answers to a combination of a 6 question questionnaire and a separate 384 item questionnaire (!), and showing their attitudes and beliefs about their creative abilities:

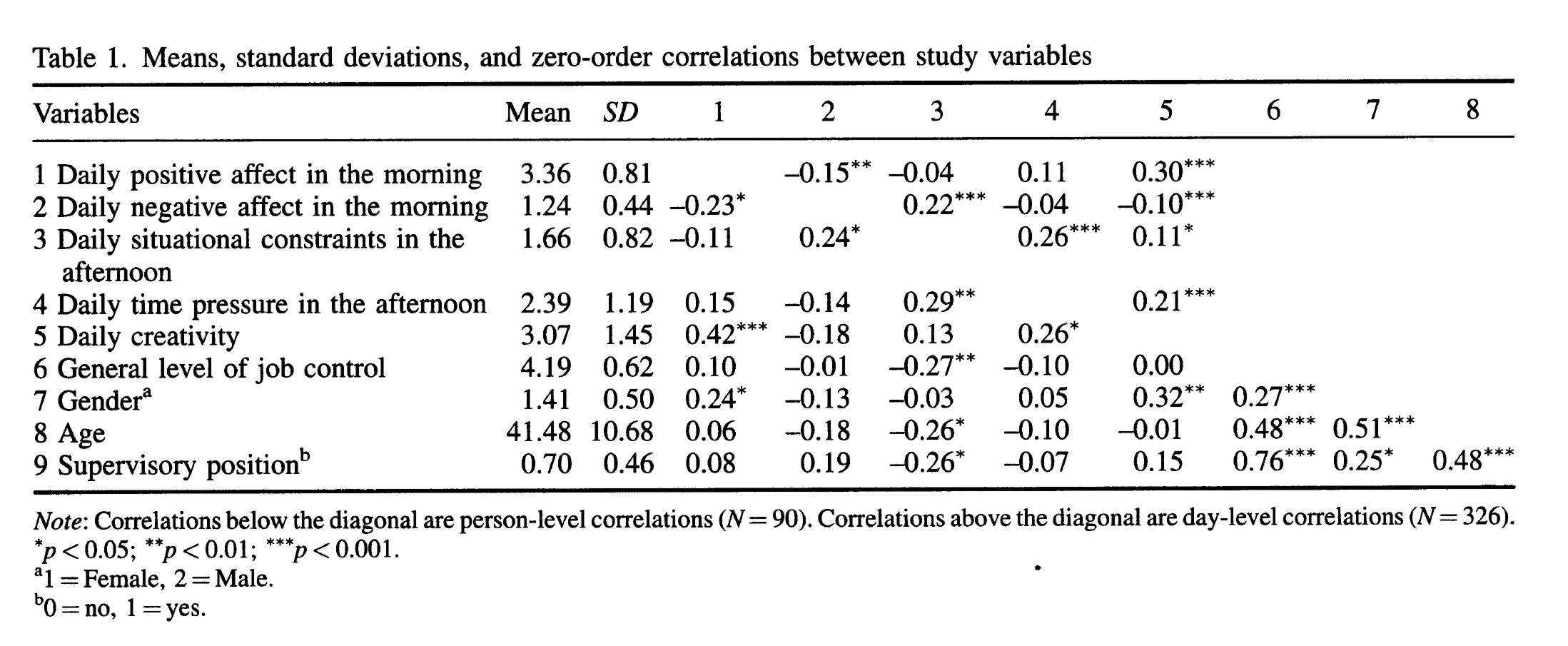

Here is a table excerpted from a paper about the way job stressors and job control impact creativity, showing the relationship between time of day and when people feel creative:

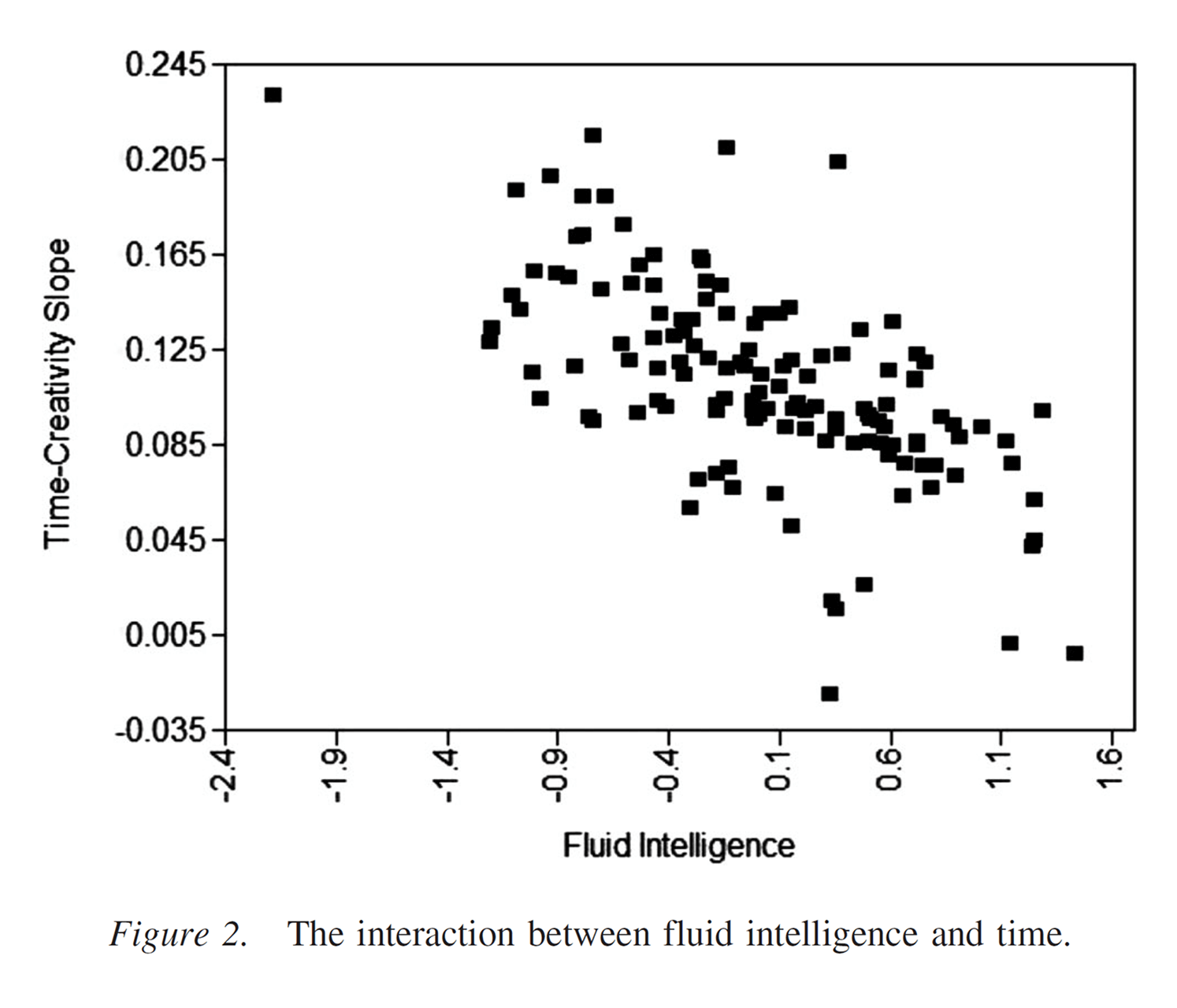

And here is a chart excerpted from a paper about why ideas get more creative over time, showing the relationship between how smart someone is and how much time it takes them to be creative:

The frameworks are the results of experiments, empirical approaches used to identify how creativity "works", and to prove that someone is more or less creative, or their output is more or less creative, based on certain circumstances.

There are three parts that make up most of these endeavors of experimentally finding validity and truth in creativity. The first is the experiment itself, which generates data. The second is identifying some meaningful result in the data. And the third is relating that meaningful result back to a part of creativity, often with a focus on innovation and the creation of something new and unexpected. The experimental designs described in these articles are usually quite sound, with a stated hypothesis and theoretical grounding, a formal and repeatable structure, isolated variables, defined treatments, randomly selected participants, and so-on. These well-formed experiments then successfully generate data, and that is successfully used to identify some sort of result.

And then, over and over, the experimenters plot poetry on a graph.

They say things like,

"Figure 2 depicts this interaction as a scatterplot. The X-axis is fluid intelligence; the Y-axis is the size of the time– creativity slope. As intelligence increases, the within-person relationship between time and creativity becomes smaller. In short, the serial order effect diminished as intelligence increased. People high in fluid intelligence had flatter slopes, so the creativity of their responses depended less on time. Stated the other way, people low in fluid intelligence had steeper slopes, so their responses became increasingly creative with time"

and,

"Means, standard deviations and correlations are displayed in Table 1. For calculating the correlations between day- level and person-level variables, day-level variables were averaged across the five days. Before testing our hypotheses, we examined if the day-level variance of creativity was substantial. The variance at Level 1 (days) and Level 2 (persons) can be seen in the null model (see Table 2). The variance at Level 2 was 0.883 and at Level 1 it was 1.21 1. Therefore, the total variance was 2.094, and about 58 per cent (1.21 1) of the total variance was attributable to within-person variation, whereas 42 per cent (0.883) was attributable to between-person variation."

The science is good. The statistical analysis is strong. But, as Keating says as he urges the students to destroy their textbooks,

"We're not laying pipe. We're talking about poetry. How can you describe poetry like American Bandstand? 'Oh, I like Byron. I give him a 42, but I can't dance to it.'"

My issue with these papers is in the positivist approach to researching social phenomenon. Creativity is always situated and contextual, in place, time, spirit, and person. Creativity is used to communicate ideas, explore materials, think about things in new ways, solve problems, provoke feelings, find meaning, generate humor, grieve, sooth, reflect, detach, and, of course, it is used for no use at all. And while creativity must be an event happening at a neurological level, and an event made up of motor and cognition and perception, and an event that can be formalized and understood, the pursuit of a measurement of creativity is a fool’s errand, one that falls all over itself as it reinforces a bizzare perspective of creativity as a pragmatic, cognitivist, science-like activity.

I have a feeling that, if pressed, many of these authors would recognize these "shortcomings" or even consider their work ungeneralizable to real-life situations outside of academia. But it's pretty clear why these papers are written and accepted; it's the non-healthy cycle of success in academia. I want to get or keep an academic job, and get tenured, so I achieve in the currency of the institution, which is published papers. Those papers are reviewed by others who have gone through the same system, and are reviewed based on merits that draw from science—a sound study is one that can be repeated with the same results. Research that is narrowly scoped and leverages pragmatist approaches are selected for publication; the authors learn to research and write a certain way; and those same authors go on to peer review other papers.

Short of taking the Keating approach—rip the pages out of the book! stop participating in the system!—I don't actually think there's a way of out this cycle without blowing up the whole incentive structure of research, where tenure comes from publishing lots of things. We have such strange institutionalized models around higher education, and while I hate the way the current administration is dismantling various funding agencies, I get why half of the country questions, or dislikes, funding this form of research in the social sciences and in design. Any individual study of culture that is working so hard to prove something so narrow is destined to become either a pulp science book, or a soundbite for how taxpayer money is being abused.

I like very much this quote from Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke, in response to how thin coding approaches to social science research lead to this form of positivist conclusion drawing:

“Researchers cannot coherently be both a descriptive scientist and an interpretative artist.”

During my PhD work, I'm going to try to be an interpretative artist, even if it means I get fewer things published.