This is from 2022 | 17 minute read

Should we cancel student loans? The trap of debt is a problem of design.

President Joe Biden has extended student loan relief three times, and pressure has mounted for a complete cancellation of loans. But this is a dramatic change from how the US has long-since considered student debt: for years, student debt has been considered “good debt.”

We’ve heard over and over that a bachelor’s degree leads to a million dollars or more in salary over the course of a career. Causality and correlation may be mixed up here, but that aside, the backdrop has changed. People are finally paying attention to the 1.7 trillion in student debt in the United States, describing it as a bubble and fearing the same sort of burst as we felt in the financial crisis of 2007.

As the debt bubble grows and alumni with non-vocational degrees are seen as unemployable, and as 6-year completion rates linger around 59% – we’re seeing increased media focus on debt, framing it as a problem, not a solution.

Debt is often described as a problem of government and policy, and of blame and responsibility. Some describe that students (and their parents) should know better, and shouldn’t have taken out large loans. Some blame the schools for offering degrees tied to no obvious earning potential. Others say that it’s our government’s role and responsibility to structure a system that doesn’t lead to such a burden. And still others place blame on the lenders themselves.

Another way of examining the problem is through a lens of behavior:

- Where do we learn how to save and spend?

- What are the debt products and services we use?

- How do we react when things happen related to our debt?

These are clearly design problems and so they deserve our designerly efforts. But, with care: we designed these problems in the first place. At this point, I don’t think our efforts should be spent on “solving” these problems, but instead, on framing them.

A behavioral framework for thinking about student debt will help shift the conversation from an abstract discussion of blame and responsibility to one of more healthy action.

Based on our work at Modernist with our financial customers and our education clients, we’ve developed a working model for discussing student debt behavior. This model focuses on these main insights:

- I’m following what I see others doing.

- I have no framework from which to understand mechanics or language of debt.

- I purposefully ignore my debt because it scares me.

- I think I’m buying access to a job, but I may be buying an opportunity to acquire knowledge.

I’m following what I see others doing

When we speak with university students (both just-out-of-high-school, as well as what were previously considered non-traditional, older students), we see that students are mimicking what everyone else is doing:

I select a school based on what my friends and family are doing.

This may mean selecting a community college in their immediate geographic area, because they only have limited visibility into immediate choices. For those focused on a four-year school, we see students making selections based on where their friends or siblings are going. And often, it means selecting a school based on what they see advertised on television: a for-profit, a quick-and-dirty online degree, and the promise of a credential with little effort.

I select a major based on the limited selection of what I know, which is often based on what my family has done or encouraged me to do.

Students frequently tell us that they selected their major based on what their parents do for a living. Other students describe picking a major at a major’s fair based on what their friends selected. Still others pick based on the name, because they recognize it; the word “accounting” is more familiar than “actuarial sciences.”

I pay for school based on what I see others doing, which often means taking out large loans.

Students hear over and over again that student debt is “good debt,” and they see that “everyone else has expensive loans, so I should too.” High-school counselors assume that loans are a given, and the FAFSA application is simply a rote part of the application process, rarely questioned.

In theory, this “I do what I see others doing” is not particularly problematic, because we’re social creatures: it’s unrealistic to think that someone knows what to pick on their own, and it’s a sensible assumption to think someone else knows what they’re doing. Unfortunately, it’s also typically a wrong assumption when it comes to higher education. No one seems to know how the system works, and nearly everyone assumes everyone else does.

Acting on these poor assumptions shouldn’t be a problem, because mistakes are typically recoverable. In most circumstances, we can change our mind, or try something else. But in the case of higher education, recovering from an initial mistake is a long, winding road. In the hundreds of students we’ve spoken with, we see this pattern play out over, and over, and over:

- I selected a school because it’s close to my home town.

- I selected a major based it’s what the school offered and what my friends were doing.

- I took on a ton of debt to pay for school, because everyone told me to take on debt.

- I got to my junior year and decided I hated the school and the major.

But now, it’s too late to switch. The student has burned through their financial aid, wasted credit hours that won’t count for a new major or won’t transfer to a new school, and most importantly, is demoralized with what they perceive as personal failure. They think:

The system didn’t fail me; I failed the system.

As a consequence, we often see students persevere and finish a major that they hate. They are unhappy with their final years in school, and when it comes time to find a job, their approach is lackluster. We spoke with a woman whose mother was a psychologist. The student enrolled in psychology, and late in her junior year, she finally was honest with herself: psychology just wasn’t a good fit. But she buckled down and finished the degree. When we met her, she was looking at the prospect of a career in psychology with no enthusiasm for her future. She was considering taking on more debt to go to graduate school, or simply taking a service job.

While some students finish their degree with a poor outlook, more simply drop out. They don’t perceive their efforts as a sunk cost, but instead, as a waste of their time and money. Now, they’ve taken on debt, and have no credential to show for it.

This plays out at all socioeconomic levels; it’s not simply five and six figures of debt that can burden a dropout. We spoke with a counselor at a community college, who described what she sees as a regular phenomenon. Low-income students enroll in community college, and take their required calculus class. But they are drastically unprepared for this work; in response, the school has added a remedial math class for these students. But the students are unprepared for that too, and so the school added a pre-remedial math class, with content at a gradeschool level. And students aren’t prepared for that, either.

The students will have completed a year of school, and paid for classes, but have received no college credit at all. And when their family asks them how college is going, they have to tell them: they haven’t really started yet.

This part of our student debt behavioral model describes how unforgiving academic decisions are. Sure, it’s easy to say that students can just switch directions, except the credit system and the unique requirements for each credential makes a change extraordinarily difficult to understand, much less do. And it’s easy to say that students should be better informed about their decisions before they make them – but it’s completely unrealistic to expect an 18 year old to know what it’s like to study psychology, or someone who has worked in food service for 20 years to predict the demands of night school, or someone who completed their GED in a horribly performing district to understand what to expect in community college.

The problem is not that students are making uninformed or poor decisions. The problem is that the system is unforgiving of those decisions. It does not allow students to change their mind. This is the first part of how a problem, and solution set, should be framed: we should design educational products, services, systems and policies that help students change their minds.

I have no framework from which to understand the mechanics or language of debt.

Debt seems simple. You borrow some money, and then you pay it back. But for any of us who have ever taken out a loan, we know it’s much more convoluted.

This is a student loan statement from a student we spoke with:

The student is studying a difficult degree at a demanding school, and clearly has the capacity for critical thinking. We asked her to explain the statement; she struggled. She couldn’t tell us what any of the words on the page meant – even the ones that seemingly make sense. Some of her questions included:

- Why are there so many loan dates, if I just took out one loan?

- What’s a consolidated loan? What’s an unsubsidized loan? What’s a subsidized loan?

- What’s the difference between an outstanding principal and outstanding interest?

- How much do I actually owe, and how much will I end up paying?

This is another statement, from a student studying finance:

Again, a thoughtful, critical thinker – who was literally taking finance classes – couldn’t explain a majority of the page. His questions included:

- Why are there different groups?

- Why are there different interest rates?

- Why is the loan already accruing interest, if I’m still in school?

The students don’t understand the words on the page, which is a problem. But what’s worse, they have a massively oversimplified mental model of how debt works. There are complexities to compound interest, to variable interest rates, to amortization, and to forbearance, and the difficult language hides even more difficult concepts. A simplified understanding of the system may be the only way students can understand anything about debt.

Most of us have oversimplified mental models of how systems work, and that simplification helps us get through our day with ease. I don’t need to know how electricity works to know that when I flick a switch, my light goes on. I don’t need to understand how a drug works to know that when I take it, I get better. And I shouldn’t need to know how a loan works to benefit from it.

I trust that the electricians did a good job, and that the city-employed code inspector made sure of it. I trust that the doctor graduated from a well-respected school after years of training. And I trust that my loan is in my best interests. And, simply, it isn’t. Major lawsuits describe deceptive loan practices in a poorly regulated industry, such as the many suits against Navient and the settled case against Career Education Corporation.

We should design educational products, services, systems and policies that help students experience debt using models, language and metaphors they understand and can relate to.

I purposefully ignore my debt because it scares me.

Debt causes anxiety. One of the primary ways we see students deal with the anxiety is to completely ignore their debt. If the debt is out of sight, it’s out of mind, and the negative emotions dissipate.

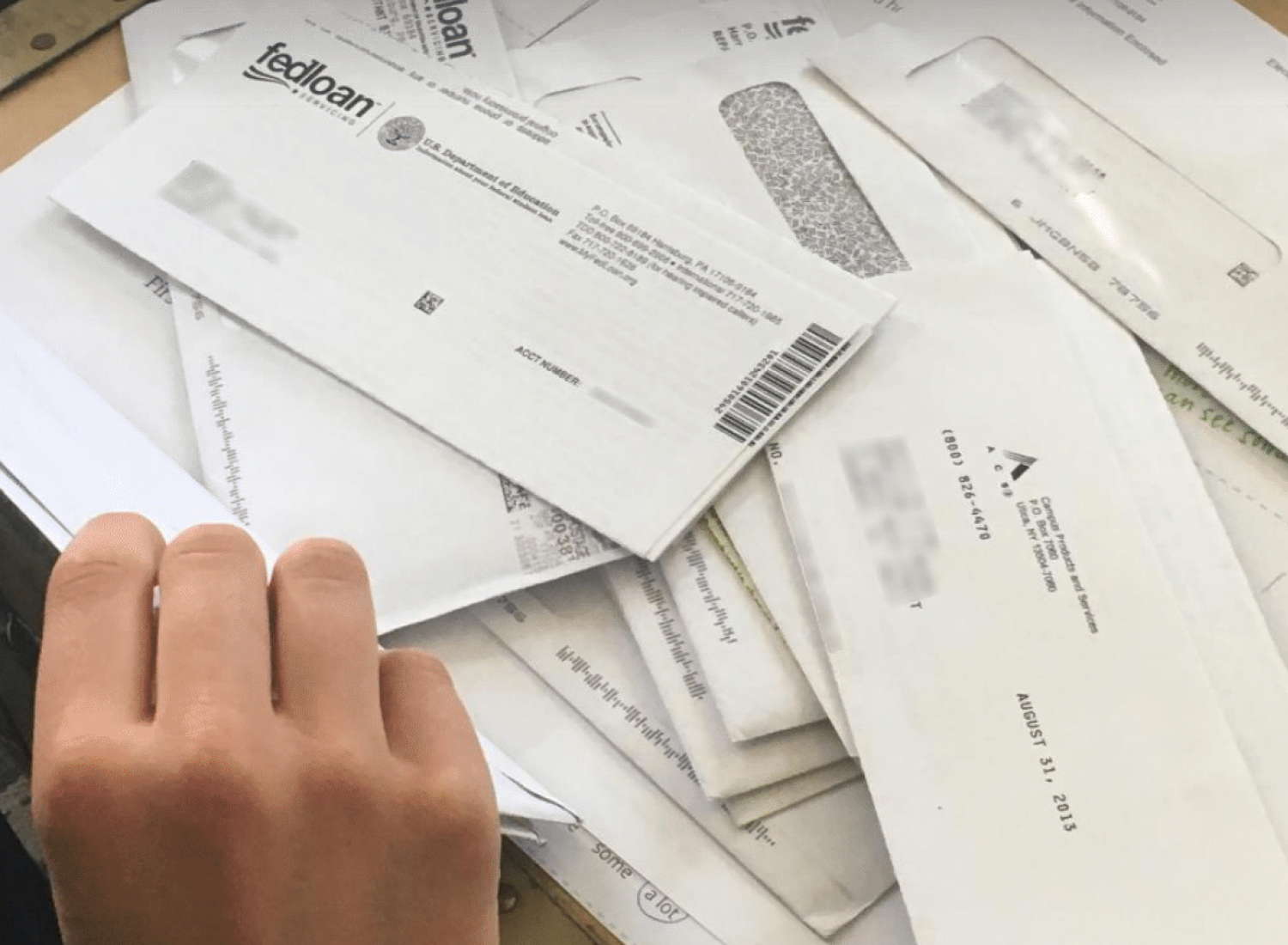

One of the most vivid examples of this was a student we spoke with who carried debt from her undergraduate degree at Oberlin. We met her at her apartment, and before we arrived, we asked her to gather her information related to her student loans. When we arrived, she had a pile of unopened envelopes on her table.

These were her debt notices that she had accumulated. We asked her why they weren’t open, and she told us:

It just freaked me out to have it subtracted from my bank account every month, all these late payments, because I wasn’t able to manage it. I was so terrified, I had this shoebox full of past due notices, and I just didn’t look at it… I’d pay them some months, then because I wasn’t having them automatically deducted, I’d get these letters. I wouldn’t open the letter, and then I’d forget about it, then not pay at 3 months at a time. It was just really scary.

We opened the envelopes together. Our research was conducted in late 2016; the notices were dated 2013. She was three years delinquent on her payments. And as she learned this, her response wasn’t fear or concern; it was shame:

It’s kind of embarrassing for me to tell you guys this stuff. I also don’t know you so I don’t really care that much. But I wouldn’t tell other people this. Like anyone. And I think that’s one of the worst things about it. My friends know that I have student loan debt, and I know they have debt, but no one talks about how fucking scary it is, or about actually what shit means.

The gravity of a large loan feels intangible. What does it mean to have $70,000 in debt? $80,000? Paying off such a large amount seems impossible, and so ignoring it entirely is, emotionally, just as good a strategy as chipping endlessly away at it.

As a result of ignoring debt, students and alumni seem to have what looks on the surface like a cavalier attitude to money. But the casual approach to savings and debt is rooted in a real sense of guilt. They describe an undercurrent of buzz and unhappiness as they spend without considering long-term consequences. This is intertwined with the idea of “fear of missing out.” Why take a conservative attitude now, when, for all practical purposes, students feel unescapably screwed in the future? They might as well live in the moment and have positive experiences instead of working towards something that seems unattainable.

We should design educational debt products, services, systems and policies that minimize shame and isolation, and that help students see how even small, short-term actions will lead to larger-term benefits.

I think I’m buying access to a job. Schools think they are selling access to learning.

Most consumer products are, by and large, forgiving. Electronics come with warranties. Stores have return policies. Companies offer money-back guarantees. Even the most obtuse and poorly designed consumer product has a way out: we can eventually get even the obnoxious customer service representative at Verizon to cancel our account.

Imagine that you hear from your friends that there’s a brand-new service called Netflix that allows you to watch Game of Thrones. You sign up for $9.99, log in, search, and realize that the show isn’t a choice. So, you aim your frustration at Netflix and cancel your subscription. You are out a small amount of money and are slightly annoyed, but you’ve easily undone your decision. You move to another service like HBO.

In this situation, Netflix presented a value promise – the ability to watch shows – and, from your perspective, it didn’t deliver. As a result, you cancelled, and the exchange was over. We “vote with our money” – and if enough people experience that value-promise disconnect, the service will adapt, or it will fail.

Students (and parents, and legislators, and guidance counselors, and a large part of the media) view education as a consumer product, and expect a consumer value exchange. All signals to incoming students lead them to believe that they are buying a promise of a job. For younger students, guidance counselors and parents push education as a way out of poverty or service jobs. Community colleges promise either vocations or clear pathways to four-year institutions, so students can get jobs. Older students who are working see education as a way to improve their career paths and earn more, and for-profit schools promise access to jobs. And increasingly, the media is highlighting a need for obvious and tangible return on any educational investment. Articles constantly hammer on fine art and the liberal arts as being poor degree decisions, because these alumni are perceived to be unemployable.

But society at large has a romantic and nostalgic perspective of higher education as a place people go to learn. It is, we feel, a place of purity of knowledge. State and private non-profit institutions describe their missions in terms of learning, knowledge acquisition, and discovery.

The mission of The University of Texas at Austin is to achieve excellence in the interrelated areas of undergraduate education, graduate education, research and public service. The university provides superior and comprehensive educational opportunities at the baccalaureate through doctoral and special professional educational levels.

The university contributes to the advancement of society through research, creative activity, scholarly inquiry and the development and dissemination of new knowledge, including the commercialization of University discoveries. The university preserves and promotes the arts, benefits the state’s economy, serves the citizens through public programs and provides other public service.

Faculty at schools like UT celebrate curiosity and knowledge production. 4-year institutions, Ivy and state school alike, think they exist to provide access to learning, and the value proposition is: pay us for this access.

There’s a fundamental mismatch. If educators are structuring classes around a purity of knowledge acquisition, and students are expecting to acquire specific skills suitable for employment, everyone’s going to be disappointed. Faculty see that students aren’t interested in or motivated by traditional forms of inquiry. Students don’t see the relevance in the material they are learning. Administrators track outcomes related to completion and job acquisition. Faculty look for students to grow their curiosity and passions.

Eventually, students discover this mismatch. But by the time they realize they aren’t buying what they think they are, years have gone by, thousands of dollars have been spent, and instead of blaming the school, students blame themselves.

We hear this not only in our student research, but in our research with faculty, too. The tenured faculty we engage with largely don’t like the commercial focus of education and the emphasis on jobs. They feel pressure to change their curriculum to be more vocational, to track quantitative metrics of learning progress, and to see students complete their credentials. They describe a lack of administrative support for encouraging students to explore, to follow their curiosities, and to take a more organic approach to knowledge acquisition. And many don’t like what they are seeing – they feel that academia is increasingly losing its purity, its integrity, and its cultural relevance.

Somewhat ironically, the predatory for-profits – who are most under fire for their poor graduation rates and high tuition – are much more direct in describing their value promise in terms of jobs:

University of Phoenix provides access to higher education opportunities that enable students to develop knowledge and skills necessary to achieve their professional goals, improve the performance of their organizations, and provide leadership and service to their communities.

The behavioral insight is around clarity of value. We should design educational debt products, services, systems and policies that make a clear articulation of value, and then deliver on that value proposition.

A Design Framework for Student Debt

We’ve developed this behavioral model to help us better discuss and consider the ecology of student debt.

Students repeatably hear that higher education is the way to higher earning potential, and so they take on large amounts of “good debt” that they don’t really understand. They are assured by friends, family, and figures of authority that they will have an opportunity to pay it off soon after graduation. As they progress through their academic journey, they realize that the course of study they’ve selected isn’t a good fit. But it’s too late to change directions without taking on even more debt, and as a result, many drop out. Because these students have no real mental model in which to consider finances, they try to minimize their anxiety by ignoring their debt entirely. And so it compounds as their earnings do not.

In response to that, we should design educational products, services, systems and policies that…

- help students change their minds;

- help students experience debt using models, language and metaphors they understand and can relate to;

- minimize shame and isolation, and that help students see how even small, short-term actions will lead to larger-term benefits;

- make a clear articulation of value, and then deliver on that value proposition.

This model helps us frame the problem of student debt from the perspective of behavior and emotion. This adds a unique layer to a discussion that typically focuses only on politics, policy, and blame. Policy changes do not change a fundamental mismatch in educational promises, a lack of understanding of financial obligations, and a set of outdated assumptions that are spoken as truth. For these, we have design: we can change behavior, attitudes, and emotions slowly, but purposefully, through a thoughtful and systemic approach to problem solving.