May 21, 2025 | 2 minute read

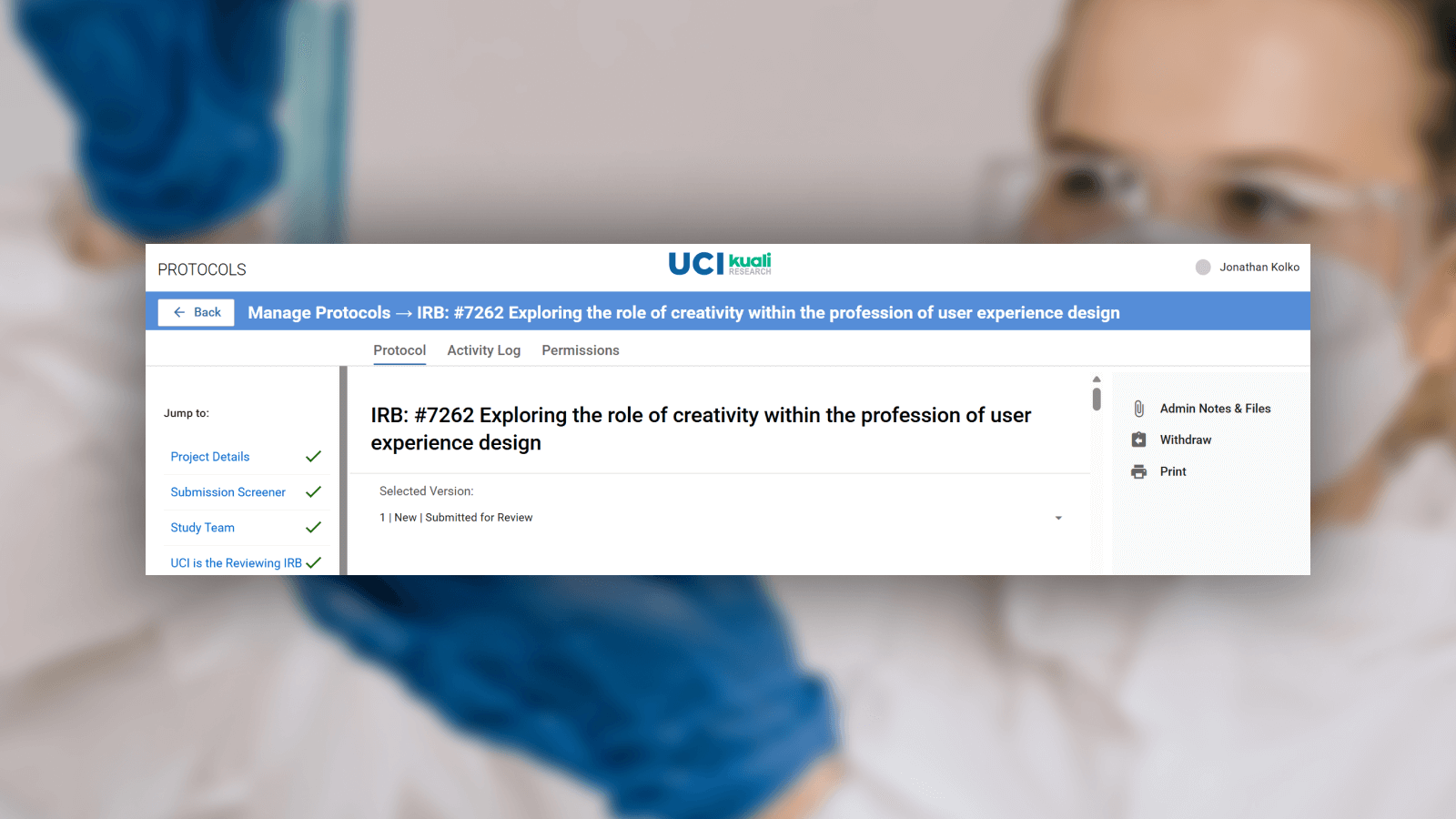

I submitted my first study to the IRB for approval.

Since I have some down-time before starting officially, I decided to spin up a research study; when I met with Paul and Katie in March, Paul recommended getting some data to work with as quickly as possible. It's reasonable, because it will move any conversation and learning experience from discussion to applied, which I value a great deal more.

The study is focused on exploring the role of creativity within the profession of user experience design. This is motivated by a few of my curiosities, triangulating.

I'm convinced that interaction design is becoming a commodity because it's been conflated with and polluted by User Experience design, and judging by the response to this article I wrote, other people are convinced and worried about it, too. I don't yet intend to validate the assumption, but I do want to gather data to further explore why other people hold the same assumption.

I also want to better understand why, when I teach, some people are more comfortable with doing "creative" activities, and as a result, increase their abilities to make things. Part of this is understanding how creativity is broadly discussed in the world, and in industry. Part of it is understanding the context in which creativity happens, and the external pressures that surround any activity of making. And another part is understanding the way design is being taught right now, a lot of which is coming through bootcamp programs.

I also want to gain experience working through the machinations that are academia's review process to start a study, because I've never done it the "right" way before. This is the way I will work with my advisors, but mostly, how I'll work with the IRB and the school itself.

And, I'm going to try a hybrid combination of the reflexive thematic analysis I've been reading about, and Gee's discourse analysis for data analysis.

It will be nice if there's publishable results at the end, but that's not a real goal here.

I found the process to be really no different than when we write research plans with clients, except that it was then populated into the IRB tool. This also wasn't too arduous. I can imagine that, if I was doing something with real risk for participants, the process might become reallllly elongated, although for the right reasons.

Here's some details from the study plan.

Background

This research is based on an overarching assumption that the relationship between practicing user experience designers and creativity has undergone a fundamental change in the last decade, a change that has placed increased emphasis on assembly and has simultaneously devalued creativity.

Here, creativity means:

- Designing new methods and techniques that are unique to solving a specific design problem,

- Producing design artifacts and design solutions that selectively deviate from any accepted standard or precedent, or

- Proposing designs that are surprising, or that partially ignore business requirements and technical constraints, or that cause stakeholders and decision makers to question their assumptions.

This shift may have benefited organizations, who can now streamline the production of their digital products. But as a result of this shift, the discipline of design has lost out in three ways. First, the things that are being made are lacking in uniqueness, which results in a commoditized look, feel, and user experience across products and companies. Next, usability–which is highly contextual to specific interaction instances–has been deprioritized, as its context-dependency disrupts the reuse of modules and components. Finally, designers have become disappointed with design as a whole, causing them to lose satisfaction in their jobs and to leave the discipline entirely.

This relationship was, and is, multi-dimensional and complex, but assumptions about the major vectors of the change include:

- The way designers are being trained has changed. There has been a proliferation of “bootcamp” style design educational offerings, which are often much shorter than the education a student would receive at a traditional design school, and as a result of the shortened program length, they teach methods and the use of software tools but do not emphasize creativity

- The tools and processes used in industry have changed. Medium- and large-sized businesses have established modernized design language systems, which manifest as a) a set of reusable interaction and visual design components and controls and b) a governance model that dictates the usage of these elements (and vastly limits the ability of a designer to add to or change the elements)

Designers who are in a hiring manager role have years of experience evaluating portfolios based on older educational models, and as a result, they look for creativity and concept exploration when they are hiring new candidates. These managers also have worked with unmodernized or non-existent design systems for the majority of their careers, and as a result, have had objectively less time to learn to value and use these systems effectively.

If these assumptions are correct, hiring managers, then, are stuck in an awkward position. Modern design language systems enable designers to use and assemble existing things and essentially “disable” (or discourage) designers from creating new things. Portfolios from junior candidates now often reflect their shortened bootcamp-style education, which emphasizes the use of components and controls, modularity, and assembly, rather than creativity.

But hiring managers themselves have been taught to value imaginative creativity and the pursuit of newness–and to look for those qualities when hiring. They must now decide if they should abandon the creative foundation of their design training in order to hire, or if they should continue to place value on uniqueness, and therefore delay or entirely defer hiring, which has a measurably negative impact on a business’s performance.

The goal of this research is to inform, and therefore refine, these assumptions. This, in turn, will help design educators either tailor their pedagogy and course content to better serve the vocational demands of business, or change the intended outcomes of their teaching in order to move away from design in a business context.

Research Questions & Hypothesis

This research approach formalizes the above assumptions into two hypotheses that are related and also somewhat in conflict with one-another.

Hypothesis one:

Design managers in mid-sized and large corporations, pressured to ship products with assembly-line efficiency and speed, deprioritize a candidate’s creative abilities when they are hiring junior-level user experience designers.

Answers to the following questions will help inform this hypothesis:

- How do design managers define and value creativity in the context of their organizations?

- What qualities and attributes do design managers look for when they hire junior talent, and how do these relate to their definitions and valuing of creativity?

- What do design managers feel has been the impact of design language systems, Figma, reusable components, token-based design, and other aspects of “assembly design”?

- When hiring junior talent, do design managers value standardized design skills (such as following an established process, using an existing method, selecting from an existing set of user-interface components, leveraging established interaction patterns, creating a “safe” or “conservative” solution to a problem, accepting established assumptions, and following requirements), or inventive design skills (such as creating a new method, producing an unexpected and novel solution to a problem, designing a new user-interface component, challenging existing assumptions, and questioning requirements)?

Hypothesis two:

When design managers in mid-sized and large corporations evaluate the portfolios of junior-level user experience designers, they don’t see adequate evidence of creative abilities to hire the candidate.

Answers to the following questions will help inform this hypothesis:

- What are design managers looking for in a portfolio, in order to indicate to them that a candidate has creative abilities?

- Do design managers feel that schools are adequately preparing designers for junior-level user experience jobs?

- Do design managers expect a junior designer to be creative in their organization?

- How do design managers describe the quality of the talent pool of potential new hires?

Method & Approach

Overview

Data for this research will be gathered through a semi-structured 1:1 interview between the researcher and a design manager. Interview data will be analyzed using a reflexive thematic analysis; through this analysis and synthesis, the researcher will highlight patterns, anomalies, and key findings.

Participants

The participant base will include:

- Between 15 and 30 participants

- Established practitioners, with senior titles that indicate their influence and impact on decisions in an organization (such as design manager, design director, creative director, and vice president)

- Practitioners from mid-sized and large digital product organizations (excluding consultancies or agencies) with more than 250 employees

Recruiting & Scheduling

Participants will be recruited via a public post on LinkedIn. Text for the post is provided in the Appendix.

Scheduling of research sessions will be coordinated via email. Participants will be provided an opportunity to select a time convenient to them. Research sessions will last for approximately 90 minutes.

Interviews & Data Collection

Interviews will be conducted via Zoom. The researcher will facilitate a discussion centered around these topics:

- Personal background & information (title, role, tenure at company)

- History of their design education and training

- Company information (size, organizational structure, products, culture and “creative vibe”)

- Views of creativity in the context of their workplace

- Qualities, skills and traits that are desirable when recruiting and hiring junior talent

- Hiring approach; role of portfolios, case studies, skills, methods; use of rubrics or formal evaluation guidelines, vs informal assessment criteria

- Perspectives on design education and preparedness of students

- Perspectives on design changes and trends in industry

- Discussion of the role of design language systems, components, controls, and other “assembly-like” aspects of modern software production

Data Analysis

A hybrid analytic approach will be used to analyze and synthesize the research material, combining reflexive thematic analysis with discourse analysis based on James Paul Gee’s framework. This method allows for both the identification of recurring themes and the examination of how language constructs social reality, power, and identity within the context of design practice.

First, categories will be developed in a bottom-up fashion through visual affinity mapping of similar utterances across interviews. These categories will be initially framed as action-oriented statements from the perspective of a hiring manager (e.g., “I ask questions in interviews related to the use of visual design methods”). These statements will then be grouped into broader insight themes—interpreted as patterns in how hiring managers describe the evaluation of creativity, the role of design systems, or their perceptions of junior talent.

Next, individual transcript segments associated with each theme will be re-analyzed using Gee’s 7 Building Tasks of language: significance, practices, identities, relationships, politics, connections, and sign systems and knowledge. This discursive layer will help surface how participants construct meanings, assert values, and position themselves within organizational hierarchies and cultural shifts in the design field.

A narrative of findings will combine these discursive insights with supporting quotes, demonstrating both what was said and what saying it accomplished. These findings will be compared to the study’s original hypotheses and used to critically reflect on assumptions about creativity and professional evaluation.

The researcher’s positionality will be explicitly described, including how their own background in design informs the framing and interpretation of both thematic and discursive patterns.