This is from 2015 | 27 minute read

Leveraging Design Research to Empower Students

Abstract

This paper presents the results of a quantitative and qualitative research study conducted in Texas with users of the popular MyEdu system, a free online service that helps students manage college and find a job or internship. The statistically significant survey of college students, and the associated in-depth ethnographic research, indicate four major findings:

- Students do not feel as though they are receiving logistical or emotional support and advice as they make large academic decisions (such as the selection of a major or the desire to change majors mid-stream);

- Students’ large, academic decisions are often made irrationally, based on anecdotal data or on a whim;

- These large, academic decisions are made early in the academic journey, where students may have an incomplete understanding of what they are doing and why they are doing it; and,

- These large, academic decisions have tremendous emotional and financial consequences for students and society.

Fundamentally, the research indicates a divide between the desire of students to explore academia in a flexible manner before committing to a course of study, and the desire of academia to force students through a rigid and rather unforgiving set of procedures quickly and efficiently. Following our research findings, we offer several ways that technological advancement can play a role in humanizing the student academic experience, emphasizing a comprehensive solution, rather than a single point-solution focused exclusively on online-learning.

Introduction

Large public colleges and universities have a unique goal: to broadly educate citizens in a variety of subjects, at an affordable cost, without placing an undue financial burden on the citizens of the municipality or state. While some students pay full price for their education, higher education is typically subsidized through a variety of sources, including private funding, research grants, philanthropic fellowships, and—of course—taxes. As would be expected, then, the landscape of higher education becomes a political battleground, with multiple opinions and values creating complexity and undue bureaucracy. In many states, higher education has become the main stage for an ideological conversation concerning the cost of a degree, the amount of time students should and do take to graduate, and their social contribution, in terms of employment, upon graduation. (Lewin 2013)

At the heart of this debate is technology. The broad idea is that digitization and connectivity, open access to content, and various delivery platforms (some commercial, and others free and open) will serve to democratize learning, reduce costs, and improve graduation rates. The “MOOC”—the massively open online course—has been offered as the silver bullet to astronomical student debt, miserable graduation rates, poor student performance, disproportionate student to teacher ratios, and poor faculty performance (Waldrop 2013). A MOOC is not ideological—it is an actual functioning platform for educational delivery—but it has, at its core, an ideological stance: that education can and should be scaled broadly, and that technology is a good and sound environment in which learning can occur. Much of the debate of MOOCs, if there can be said to be much debate at all, surrounds this point: if the computer is a good delivery mechanism for learning, and if it can “replace teachers.” (Landers 2012)

Yet what is lost in the ideological debate of MOOCs and online learning is an understanding of the actual students that are taking so long to graduate, wasting so much of their own and taxpayer’s money, and graduating without employable skills. Course delivery is a key part of the college experience, but it is only a part of that experience. A focus exclusively on the technological delivery platform ignores conversations of services, policies, and the various supporting analog infrastructure necessary to help alleviate emotional, logistical, or tactical problems faces by students. A focus exclusively on content delivery effectively “punts” on the ecosystem conversation of higher education: it emphasizes a tree, but ignores the forest.

The forest is huge, and at public universities, it is thick with weeds and arduous to navigate. The data from this research study illustrate that the actual delivery of content to students is but one of dozens of problematic touchpoints in the larger context of the massive public university and college experience. Somewhat ironically, we feel that less in-vogue technological solutions can drive a tremendous impact in these other areas of pain, having a dramatic impact on the student academic experience and positively influencing graduation-rate and graduation-cost. These solutions make up a strategy that a) proposes a less dramatic and permanent focus on “major selection”, b) capitalizes on computational ability to offer personal education plans rather than generic degree audits, c) helps students understand the relationship between unique skill acquisition and potential career paths, and d) makes obvious the relationship between skills, career outcomes, earning potential, and the cost of learning. We call this strategy “Return on Education, ” or ROE.

Research Methodology

While our broad thesis surrounding Return on Education is based on our experience with within educational technology, the specifics surrounding our insights and conclusion in this paper are based on a two-prong research study, conducted in Q4 of 2012 and Q1 of 2013. At MyEdu, we use this type of research to inform our products and to help us understand and empathize with our student users. More specifically, the results of the research help identify gaps in our product functionality, guide us in our product roadmap sequencing, help us refine the way features work, and help us to better relate to the wants, needs, and desires of our users.

Quantitative Survey Data Collection

MyEdu makes available a series of free tools to college students. One of these tools is the “student profile”, a visual resume. At the date of this survey, 300,677 MyEdu users had used this tool to create their student profile. We randomly selected 61,931 of these students, or approximately 20%, and notified them via email that they were eligible to participate in a research study. 1047 students responded by following a link to an online survey, where they completed eight questions about their academic experience. Participants who completed the survey were entered into a drawing for a $50 gift card.

Survey respondents were generally spread evenly across populations of pre-freshman, freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, and students who have already graduated. Participants included a mix of majors, schools, and physical geographic locations (although participants skewed towards Texas and California). The results of our findings are presented where n=1047, at a 95% confidence level, with a confidence interval of +/- 3.2.

Qualitative Survey Data Collection

Our qualitative research team was made up of three researchers, including the author and two mid-level design researchers. These individuals have experience conducting a particular form of qualitative research called contextual inquiry—a form of in-context, immersive interview—in order to understand and empathize with students of varying levels and experiences (Holtzblatt and Jones 1993). We visited with fourteen college students in their homes or dorm rooms. All students were attending colleges and universities in Texas. Each session lasted approximately three hours. During these sessions:

- Students were asked to describe their college experiences at a broad level.

- Students were asked to visualize their academic timeline, using blank timeline artifacts as prompts. For example, students were asked to identify key moments in their educational experience that were particularly memorable, happy, or sad, and to plot them relative to one another. Then, a discussion was held about each plotted memory.

- Students participated in participatory design exercises intended to evoke emotionally rich anecdotes. For example, students were given a variety of general photographs (a woman crossing the finish line, a man crying) and asked to select images that best represent how they felt at various points in their college experience, such as the beginning of freshman year, or upon returning from an internship. Then, they were asked to explain why they picked these images, and what they represent.

- Students were asked to show our research team a variety of artifacts they used to support education, including their physical and digital products and tools. We asked them to show us what was in their backpacks, their bookshelves, and the digital contents of their laptops or phones. Then, we asked them to explain the utility and emotional connection to the various artifacts and content.

- Students were asked to show our research team various administrative tools used at their respective universities, including online scheduling tools, course audit software, and various learning or classroom management systems. They were then asked to describe how frequently they use these tools, to show how they use them, and to describe their emotional response to the tools.

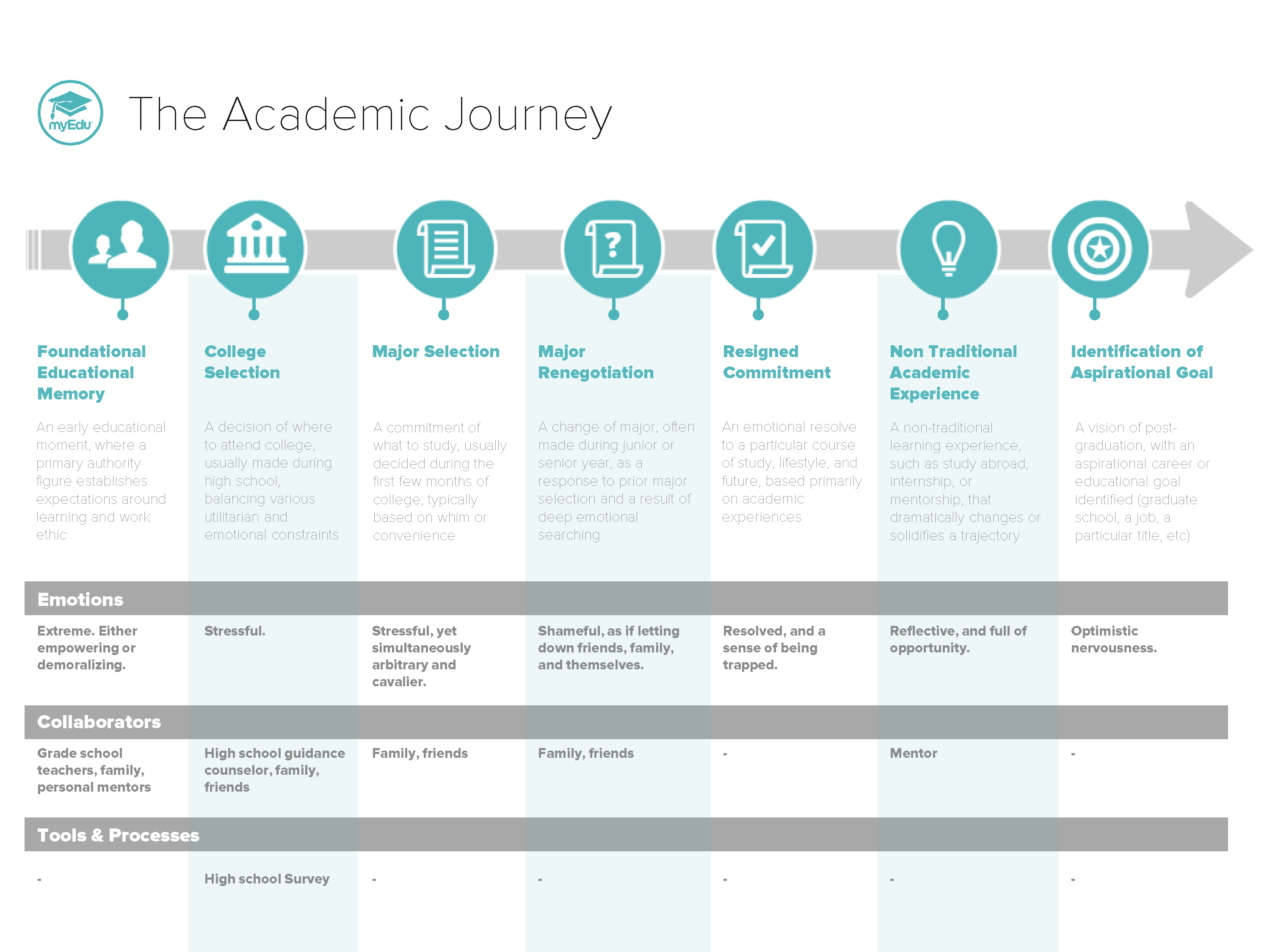

The results of the quantitative and qualitative research were analyzed in order to identify patterns and insights. Collectively, this was then used to produce an Academic Journey Map: a visualization of the journey our participants experienced during their college experience.

The Academic Journey Map

Our research identified that students generally move through six phases during their undergraduate educational experience. These phases seem to be highly emotionally charged for students. Moreover, it appears that there is a relationship between the presence of the phase in a student’s journey and the cost and time it takes that student to graduate.

We capture these phases on an academic journey map: a visualization of the educational experience, over time, that emphasizes experiential touchpoints imbued with emotion. These phases include:

- Selection of a College

- Selection of a Major Area of Study

- Renegotiation of a Major

- Resigned Commitment to a Major

- Non-traditional Academic Experience

- Identification of an Aspirational Goal

These phases are described below in further depth. It’s important to note that the academic journey map is used to present an archetypical journey for college students; clearly, individual experiences are unique, and not all students can be represented by any single model of education. Additionally, our goal and focus is on the emotional challenges faced by students, not on the pedagogical success of any given learning style. Therefore, knowledge acquisition is purposefully absent on the map.

Selection of a College

During high school, and sometimes as early as middle school, students described pressure to select a college. This selection was based on a number of factors, many of which were circumstantial and not academic. For example, some students selected colleges simply because they were geographically located in a distant proximity from their parents, providing them a feeling of freedom. Others selected schools because their friends or family were alumni from the given institution. One high school participant described that he was going to go to Huston-Tillotson University, a small college in Austin, because his grandmother went there years ago, and she would “talk to some people” on his behalf. Another student described why she selected University of Texas: “UT was just the right distance from home, to be honest. It was just me and my mom for a while, and so I’m far enough away that she can’t just show up on me, and I’m close enough where if I need to go home, I can…”

The selection of a college has impact later in the journey. For example, some students realized that a particular school didn’t offer a particular course of study only after they had begun attending that school. Samantha described that “I didn’t even want to do MechE; I wanted to do biomedical engineering. When I got to UTSA, it wasn’t available. So I randomly picked mechanical engineering because I had a lot of mechanical engineering friends.”

Selection of a Major Area of Study

Perhaps the most anxious part of the academic experience for the students we spoke with was the selection of a major course of study before, or during, freshman year. Students described selecting majors based on little or no rational data, and feeling as though they were trapped with their decision. One student described “running out of time” in the major selection process, and so she selected Accounting because it was “at the top of the list” (it started with the letter A, so it appeared at the top of a list of business majors.) Other students mentioned selecting majors because their parents had encouraged them to pursue a particular field of study. Nancy, an 18 year old psychology major, explained that she “used to want to be a criminal psychology, but my mom said I shouldn’t do that because I wouldn’t be a happy person after three years in that job.”

Major selection seems like a permanent decision, and students described feelings of shame or stress associated with wanting to change their major later in the college journey. Trisha, a 21 year old sociology major, said “I thought since I couldn’t complete the major, I was a little dumber than everyone else.” Ross, a finance major, told us that “It’s a topic that’s pretty much on everyone’s mind in college… right now is when everyone declares their majors, so everyone is declaring majors but not feeling confident about declaring majors.”

Renegotiation of a Major

After initially selecting a major and spending some time pursuing that area of study, 56% of MyEdu users reported switching their majors, or considering a switch. This is typically a personal journey, or shared only with family members. When asked why they felt a lack of emotional support for this decision, students described a number of different relationships with their advisors, ranging from non-existent (“I don’t know who my advisor is”) to authoritative (“the advisor just tells me what to do”). Students expressed desire for advisor relationships that were more personal, consistent, and meaningful. One student described that he needs “someone who is OK with helping me one on one.” 39% of MyEdu students turn to their family for help with college and career decision making, rather than soliciting help from academic or career services. 6% of students report having no-one to turn to for help in making college and career decisions.

The overwhelming reason cited for a changing in major was due to changing interests, and a lack of enjoyment in the first major selected. When confronted with the thought of switching majors, approximately 44% of students reported feeling anxious, scared, or confused, while only 13% reported feeling happy.

Students continually described feeling as though academic milestone decisions were permanent—that changing majors was emotionally charged and carried a social stigma. Students referenced feeling as though they let themselves, their parents, and their friends down by considering a change of direction midcourse. Additionally, students described feelings of anxiety related to having to stay at a school extra time (and accumulate extra financial debt) to support a change in majors.

Resigned Commitment to a Major

After experiencing a given major for some amount of time, many students described a feeling of resigned commitment to their course of study—not necessarily because they wanted to complete the degree or subject, but because their window of opportunity for changing majors had run out, the economics of a change didn’t make sense, they couldn’t find someone to help them alter their course, or a host of different emotional reasons. This sense of resignation seems directly tied to uneasiness about the short and long-term future. Students articulated worry about achieving the next perceived milestone in a pre-defined path towards success. Additionally, each milestone is seen as critical, non-optional, and a “make-or-break” moment. For example, not registering for the right classes may result in not graduating on-time. This, in turn, is seen as disrupting opportunities for an internship. Without an internship, students fear they won’t get a “good job”, and without this job, they won’t be happy. A freshman at UT told us “I think everyone wishes they had a plan. Even if they don’t have a plan, they say ‘this is my plan’, because it makes them feel good to have a plan.”

For these students, a personal advisor might be extremely useful. Yet advisors are seen as incidental, directive, or extraneous resources that are too busy to help and hard to gain access to. One student told us that the advising process “is frustrating to me because it’s hard to get an appointment—you feel lost.” Students view the educational system as a large and anonymous machine, one with systemic rules that are bizarre and often vaguely defined. They speak of the system as a necessary evil, one which adds anxiety but offers little value. Samantha, a 21 year old engineering major, explained that “college feels like a maze. I don’t know where I’m at in it.”

A Non-Traditional Academic Experience

Some students described a non-traditional experience late in their educational journey that dramatically changed their outlook on life and their academic trajectory. This experience—such as an internship, or a semester learning abroad in another country—seemed to either reinforce a good decision to change majors, or prompt a fresh set of introspection about a current course of study. While it may have been organized or facilitated by an academic institution, the experience was typically separate from the main course of study, and was often physically removed from the context of a campus. It seems that the non-traditional academic experience helps contextualize material learned in the classroom, so students can understand why they were being taught a specific curriculum or set of content.

For example, a nursing student at UT Austin described that a study abroad experience in Ghana helped her understand how nursing research can be both scientific and also political. As she described, “I did a study abroad in Ghana, and it was a huge educational moment for me. I want to do research. I need to go to grad school for my Masters in Public Health, and then I’ll need a PhD if I ever want to lead my own research.” While her initial focus and goal was to be a nurse practitioner, she has changed course as a result of her experience in Ghana. She’s now focused on higher education, because she wants to conduct academic research related to HIV/AIDS prevention in lower income populations.

Not all students have this “non-traditional student experience,” and seem to bemoan the perceived lack of direct application for their course work. One student explained her frustration with the lack of contextual applicability by saying, “I don't think I'll ever use the math I'm learning. I doubt I'll ever have to find the derivative of something—or figure out how long it takes something to get somewhere when it's traveling at a specific speed. I feel like I'm having a mid-life crisis, like I don't know what I want to do with my life.”

The Identification of an Aspirational Goal

For a small subset of students, the end of college brought about the identification of an aspirational goal. This goal—getting into graduate school, or landing a dream job—seemed related to the renegotiation of course of study and to the non-traditional learning experiences. Unfortunately, this new aspirational goal was out of reach for some students as a result of their previous renegotiation of course of study. Several students bemoaned poor grades their freshman and sophomore years, and one described her concern that she wouldn’t get into a top graduate school—her new aspiration—as a result of her poor earlier choices.

Major Areas of Opportunity

The Academic Journey identifies several major areas of opportunity—areas where technology, and new policies, approaches, and services, can demonstrate a positive impact in helping students graduate on time and at an appropriate cost. These opportunity areas are described here, to indicate how the opportunity might be addressed through a new form of platform, product, or service.

Problem

Academic decisions are unforgiving.

Opportunity

Use technology to help students predict the impact of a large academic change , or to recover from a poor academic decision.

Students feel trapped in their major, and describe a perceived social shame in changing their own trajectory. When they try to follow-through on changing their major, they feel alone and unsupported. The number of choices seems extraordinarily large, and the repercussions of a change are hard to understand and predict. For example, if a sophomore engineering major changes to computer science, they need to then understand which courses “count” for credit in the new major, what the new requirements are for graduation, when they can and should take various classes to catch up with the graduating class, and how their decision will impact their financial aid. While the complexity of this problem is hard for a 20 year old to manage, a computer can algorithmically determine the implications of a change like this with ease, and can present them in a friendly and simple way. There exists an opportunity to develop interactive systems to help students develop a personalized education plan, and for that plan to adapt to the student as they make choices and advance through their academic journey.

Problem

Students feel urgency to make decisions quickly.

Opportunity

Alter the structure of “standard undergraduate education” to allow for exploration

Students feel urgency to make decisions quickly. As a consequence, they often make important decisions (major selection, course selection, professor selection) based on a poor rationale, and regret these decisions after the fact. They feel that each choice in college determines the “rest of your life”, and students describe pressure and an urgency to constantly push forward. To counteract this feeling, the structure of undergraduate education can change to afford time for exploration, where students don’t apply directly to a major, but instead declare a major later in their academic career. This can be reinforced through changes to accreditation guidelines or to individual school policies. Additionally, high-school counselors could encourage graduates to defer enrollment in higher education for several years, and federal volunteering programs like AmeriCorps could more aggressively target graduating high school seniors.

Problem

Students make decisions haphazardly or based on uninformed advice from friends or family.

Opportunity

Use technology to help students explore the outcome of various decisions in a way that makes sense to them, and offer transparency to the family during the decision making process.

Students cite a strong familial influence in driving fundamental academic or career decisions. Many students describe how they select colleges, majors, and career paths based on off-hand comments from their parents, or based on their parents’ jobs, or based on attitudes they may have heard or learned from their relatives. This has the potential to conflict with the new-found autonomy students realize at college, leading to emotional conflicts about direction and future decision making. Digital tools can be used to help students scenario-plan potential futures and understand the impact of decisions. For example, a sophomore thinking about a change in major might digitally “try on” the different major and see how their lifetime earning potential changes, explore companies that hire for that role, or find alumni mentors who also went through the same major change. And, the same digital tools can provide collaboration mechanisms for parents to observe the various decisions as they are being formulated. Parents can play an informed role of support, rather than an influential role of directive.

Problem

College costs are unclear.

Opportunity

Provide digital tools that help students calculate the cost of a decision.

When students are selecting courses or considering a major change, cost plays a big role and has a hidden impact. Yet it’s difficult for students to predict the true cost of their education, because a decision now may have a large and unexpected financial impact later. For example, a student may elect to take one fewer required class now, because their work schedule doesn’t give them enough time to study. Yet that required class may not be offered again for a full academic year, and it may also act as a gating pre-requisite for later classes. Deferring a single class may, then, hold the student back an entire academic year, extending the financial aid burden of the student (and the taxpayers) and forcing them to graduate late. When confronted with the prospect of an extra year in college, some students may choose not to graduate at all. Software can algorithmically understand the implications of a course deferral, predict the likelihood of courses being offered in the future based on prior course data, and advise the student as to the true cost of a single decision related to course or major selection.

Discussion

This document has presented Return on Education as a synthesis of contextual and qualitative research, survey-based quantitative research, and literature review. We have two broad goals in publically sharing our strategy of ROE. First, we hope to broaden the conversation of educational technology to consider the entire academic journey, illustrating the need for a more ecology-based approach to infusing technological advancement in higher education. This means focusing on the student, rather than on policy, procedure, or technology itself, and acknowledging that the student changes during the course of their studies. It also mean recognizing that less technologically popular or exciting solutions may drive more impact as related to the cost and duration of the academic journey.

Next, we hope to emphasize the oft-ignored but highly emotional context in which higher education, and the entire discussion of educational technology, exists. The students we’ve interacted with face overwhelming anxiety related to school selection, major selection, course selection, graduation, student loans, and the seemingly critical “internship to job to happiness in life” promise. Learning has become associated with anxiety. We feel that the emotional qualities of these decisions and experiences need not be emotionally trying, and that technology can play a valuable role in eliminating anxiety during critical decision points.

Our qualitative research was conducted entirely with students in the state of Texas. Yet we see signals of our research findings within many of the large state school systems across the country, including California, Arizona, Florida, and Ohio. Graduation rates at these systems are consistently poor: for example, in 2010, only 25 percent of ASU students completed a bachelor’s degree within six years and only 7 percent finished in four years (McManus 2012). College students at these large universities are at a disadvantage, simply due to the size and scale of the school. Receiving personalized advice and support is difficult, and many students simply give up.

This is compounded by a narrative that we found almost ingrained in the millennials we spoke with. Students have been told that they are to follow a single, natural path from high school, to college, through major selection, to an internship, and finally, to a dream job (Pilon 2010). The reality, of course, is much messier and convoluted, with various life events and decisions changing the course and trajectory. Yet the academic policies and tools made available or mandated to students reinforce this one-size-fits-all mentality, and the disconnect is felt by student: when they reflect on their own experiences and compare them to the idealized versions presented, they use words to describe themselves like “behind” or “failure.”

There are large opportunities to improve the various planning, scheduling, and auditing tools presented to students to feel more human—to offer suggestions for improvement and change, and to provide help and assistance, rather than simply identifying exceptions to policy. And there exist similar opportunities to change the actual policies that guide higher education, accreditation, and graduation, recognizing that a “drive for completion” may be at the expense of “knowledge acquisition” or “acquiring life skills.”

Most importantly, we feel that there is a tremendous disconnect between the “system” of education—that is rigid, unforgiving, and focused on metrics, completion, and standardization—and the humans actually being educated. Students deserve the right to change their minds, make poor decisions, and re-evaluate their lives as they grow older, without facing massive financial or emotional repercussions from our schools. We have the technological ability to help students through their journey, if only we redirect our collective myopic focus from the panacea of online learning.

Appendix: Survey Responses

Have you ever switched majors, or thought about switching majors?

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 76 | 117 | 104 | 119 | 106 | 68 | 590 |

| No | 73 | 113 | 74 | 79 | 62 | 56 | 457 |

If you ever switched majors, or thought about switching majors, which of the following best describes why? (Select all that apply)

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My interests changed | 91 | 145 | 107 | 115 | 96 | 71 | 625 |

| My friends were in a different major | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| My earning potential was higher in another major | 23 | 42 | 39 | 40 | 33 | 25 | 202 |

| I didn't enjoy my first major | 47 | 53 | 37 | 55 | 46 | 27 | 265 |

| I wasn't learning what I wanted to learn in my first major | 13 | 26 | 23 | 31 | 23 | 13 | 129 |

| I couldn't get the courses I wanted or needed to complete my first major | 8 | 11 | 6 | 18 | 12 | 5 | 60 |

| I wanted to graduate faster | 8 | 15 | 12 | 20 | 24 | 17 | 96 |

| My family urged me to change | 3 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 29 |

| My school eliminated my major | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 21 |

| My school added a new major | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 34 |

If you ever switched majors, or thoughts about switching majors, what word best describes how you felt?

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious | 29 | 55 | 40 | 46 | 27 | 29 | 226 |

| Challenged | 25 | 33 | 26 | 37 | 22 | 13 | 156 |

| Excited | 25 | 48 | 40 | 36 | 56 | 34 | 239 |

| Scared | 13 | 19 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 73 |

| Confused | 26 | 37 | 21 | 31 | 21 | 14 | 150 |

| Happy | 19 | 26 | 26 | 29 | 19 | 13 | 132 |

| Bored | 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 27 |

| Defiant | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 15 |

Would you characterize yourself as a "traditional student", or a "non-traditional student"?

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Student | 79 | 177 | 127 | 120 | 82 | 77 | 662 |

| Non-Traditional Student | 70 | 53 | 51 | 78 | 86 | 47 | 385 |

Which word best describes how you feel about your overall college experience so far?

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious | 14 | 11 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 8 | 80 |

| Challenged | 45 | 68 | 50 | 66 | 43 | 33 | 305 |

| Excited | 26 | 50 | 39 | 35 | 36 | 18 | 204 |

| Scared | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 19 |

| Confused | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 29 |

| Happy | 49 | 83 | 51 | 62 | 52 | 49 | 346 |

| Bored | 3 | 9 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 40 |

| Defiant | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

When you think about getting a job after college, do you know how to present your skills to potential employers?

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 89 | 143 | 122 | 138 | 121 | 87 | 700 |

| No | 60 | 87 | 56 | 60 | 47 | 37 | 347 |

Who do you turn to for help with your college and career decision making? (Select all that apply)

| Pre-Fresh | Freshman | Soph. | Junior | Senior | Grads | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My friends | 22 | 31 | 23 | 30 | 14 | 10 | 130 |

| My family | 56 | 99 | 77 | 59 | 75 | 45 | 411 |

| Academic advisers | 38 | 68 | 44 | 65 | 44 | 32 | 291 |

| Career services | 9 | 15 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 69 |

| Online resources and communities | 13 | 12 | 8 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 74 |

| I don’t have anyone to turn to for help | 10 | 5 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 9 | 60 |

References

- Holtzblatt, K., & Jones, S. (1993). Contextual inquiry: A participatory technique for system design. Participatory design: Principles and practice, 180-193.

- Landers, R. (2012, 10 2). Can a MOOC Replace Your Teaching? Retrieved 3 29, 2013, from NeoAcademic: http://neoacademic.com/2012/10/02/can-a-mooc-replace-your-teaching-a-checklist/

- Lewin, T. (2013, 1 24). To Raise Graduation Rate, Colleges Are Urged to Help a Changing Student Body. Retrieved 3 27, 2013, from The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/24/education/stagnant-college-graduation-rate-is-focus-of-2-new-reports.html?_r=0

- McManus, T. (2012, 9 1). ASU battling low graduation, retention rates. Retrieved 3 27, 2013, from The Augusta Chronicle.

- Pilon, M. (2010, 2 10). What's a Degree Really Worth? Retrieved 3 29, 2013, from The Wall Street Journal: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703822404575019082819966538.html

- Waldrop, M. M. (2013, 3 13). Online learning: Campus 2.0. Retrieved 3 10, 2013, from Nature: http://www.nature.com/news/online-learning-campus-2-0-1.12590